filmov

tv

Intermolecular Forces

Показать описание

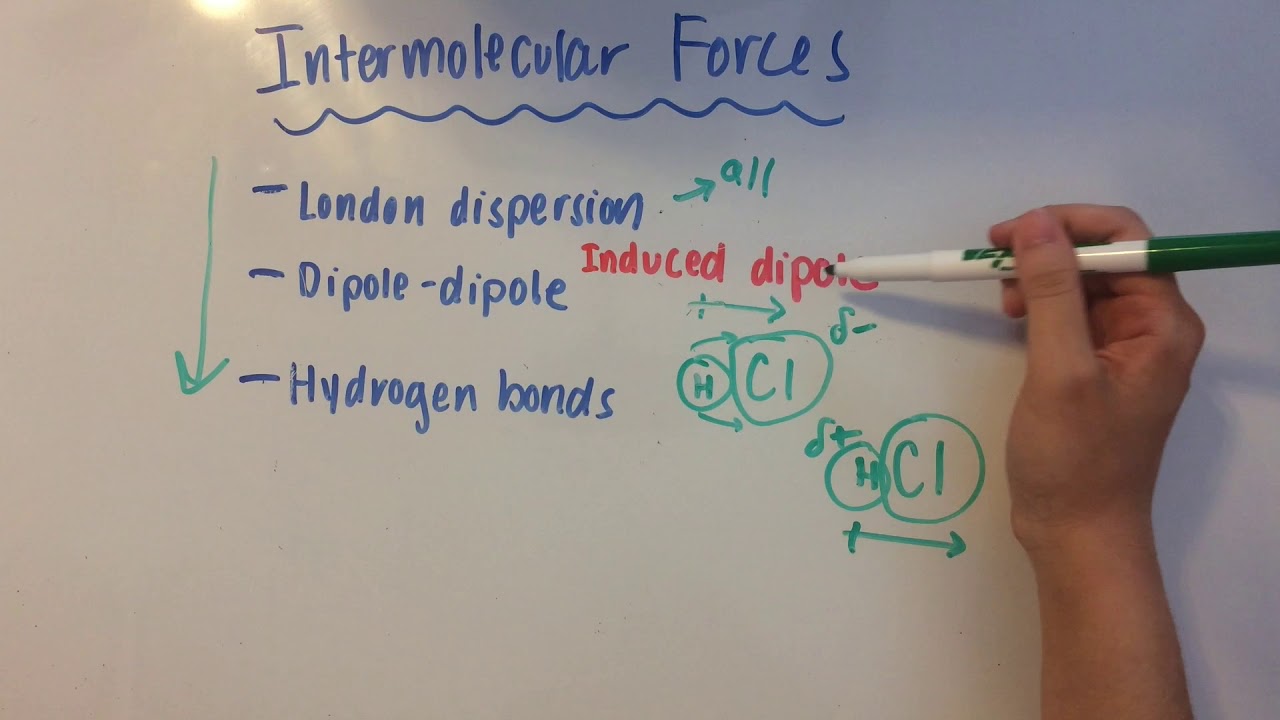

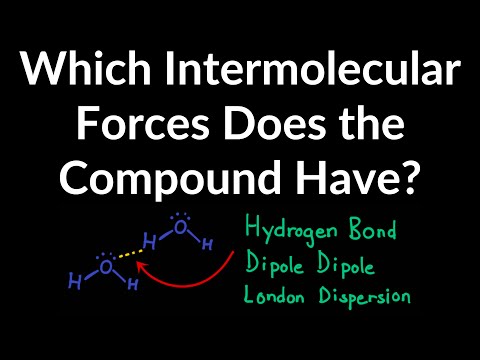

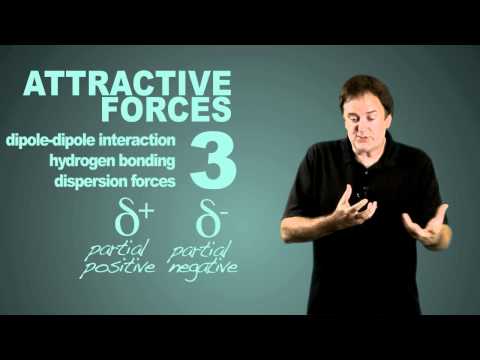

This video describes the characteristics of London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonds.

TRANSCRIPT:

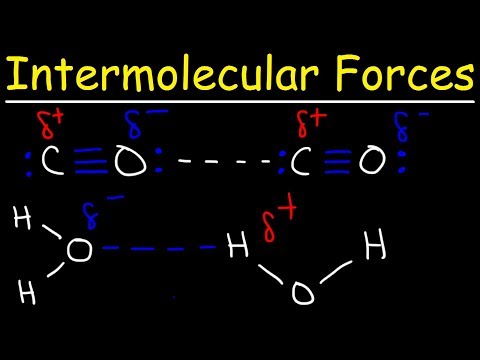

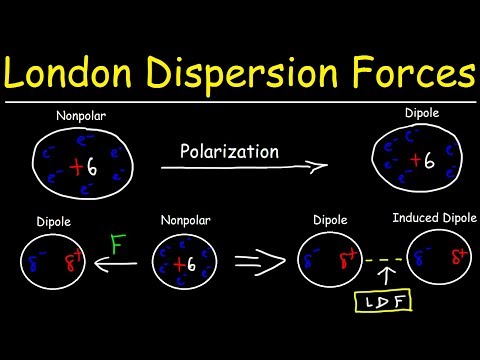

So there’s three main intermolecular forces that you need to know, and these are London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonds. And these are all listed in order of increasing strength going down. So London dispersion forces are the weakest, and they also occur in all molecules. Remember that. An example of this would be two H2 molecules. H2 is a nonpolar molecule, meaning it has no net charge. So there’s electrons moving around the H2 molecule, they’re moving and moving, and let’s say that this electron gets close to the nucleus of this one H2 molecule. This is going to create a very slight, temporary attraction between the electron and the nucleus. And that’s what London dispersion forces really describe – they’re temporary, short attractions due to moving electrons. Now we have dipole-dipole interactions. An example of this would be an HCl molecule and another HCl molecule. So, Cl is a more electronegative atom than hydrogen. So it’s going to be pulling the electrons from hydrogen closer to itself. To denote this, we use an arrow showing the flow of electrons, and you put a little cross to show where the partial positive charge is at. So hydrogen has the partial positive charge, and chlorine has a partial negative charge. We can do the same thing for this molecule. So since chlorine has a partial negative charge and hydrogen has a partial positive charge, these two will attract each other. There will be an electrostatic force in between them. And that’s what we call dipole-dipole interactions.

Now here, I’ve written induced dipole because they come in between London dispersion forces and dipole-dipole interactions. Let’s go back to our old friend H2, and we can have another HCl molecule here. So H2 is nonpolar while HCl is polar. This is going to induce the H2 into a dipole. And I’ll show you how that works. So H2 looks like this, HCl looks like this. We have the dipole for HCl. And, oops – I wrote it in the wrong direction. Let’s switch these two, say HCl is over here and H2 is over here. So since this has a partial negative charge, it’s going to repel the electrons on this side of the H2. So the electrons are going to want to move away from the Cl. That’s going to create a temporary dipole going in this direction; there’s going to be a partial positive charge on this side. And that’s going to be your induced dipole. The HCl is going to induce the H2 into a dipole. But that’s going to be for a very short amount of time, it’s going to be temporary, and it’s not that strong.

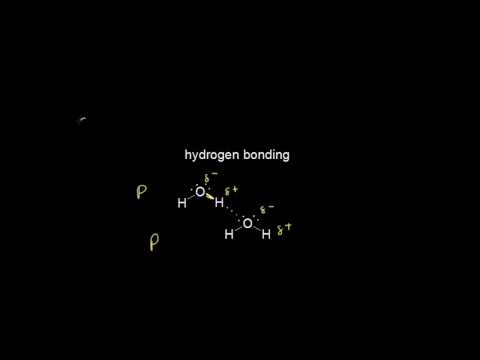

So last up is hydrogen bonds. You’ve probably heard about these in biology, or somewhere else earlier. So let me just draw two water molecules. Oxygen is much more electronegative than hydrogen, so the dipoles are going to be going this way. Same thing for this one, the electrons are going to be moving towards the oxygen. So now there’s going to be a temporary attraction between the oxygen and hydrogen, because remember, oxygen has a partial negative charge while hydrogen has a partial positive charge. So that’s what hydrogen bonds are; they aren’t bonds in between the atoms, they’re bonds in between the actual different molecules. Not between the atoms. So that’s it for intermolecular forces.

TRANSCRIPT:

So there’s three main intermolecular forces that you need to know, and these are London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonds. And these are all listed in order of increasing strength going down. So London dispersion forces are the weakest, and they also occur in all molecules. Remember that. An example of this would be two H2 molecules. H2 is a nonpolar molecule, meaning it has no net charge. So there’s electrons moving around the H2 molecule, they’re moving and moving, and let’s say that this electron gets close to the nucleus of this one H2 molecule. This is going to create a very slight, temporary attraction between the electron and the nucleus. And that’s what London dispersion forces really describe – they’re temporary, short attractions due to moving electrons. Now we have dipole-dipole interactions. An example of this would be an HCl molecule and another HCl molecule. So, Cl is a more electronegative atom than hydrogen. So it’s going to be pulling the electrons from hydrogen closer to itself. To denote this, we use an arrow showing the flow of electrons, and you put a little cross to show where the partial positive charge is at. So hydrogen has the partial positive charge, and chlorine has a partial negative charge. We can do the same thing for this molecule. So since chlorine has a partial negative charge and hydrogen has a partial positive charge, these two will attract each other. There will be an electrostatic force in between them. And that’s what we call dipole-dipole interactions.

Now here, I’ve written induced dipole because they come in between London dispersion forces and dipole-dipole interactions. Let’s go back to our old friend H2, and we can have another HCl molecule here. So H2 is nonpolar while HCl is polar. This is going to induce the H2 into a dipole. And I’ll show you how that works. So H2 looks like this, HCl looks like this. We have the dipole for HCl. And, oops – I wrote it in the wrong direction. Let’s switch these two, say HCl is over here and H2 is over here. So since this has a partial negative charge, it’s going to repel the electrons on this side of the H2. So the electrons are going to want to move away from the Cl. That’s going to create a temporary dipole going in this direction; there’s going to be a partial positive charge on this side. And that’s going to be your induced dipole. The HCl is going to induce the H2 into a dipole. But that’s going to be for a very short amount of time, it’s going to be temporary, and it’s not that strong.

So last up is hydrogen bonds. You’ve probably heard about these in biology, or somewhere else earlier. So let me just draw two water molecules. Oxygen is much more electronegative than hydrogen, so the dipoles are going to be going this way. Same thing for this one, the electrons are going to be moving towards the oxygen. So now there’s going to be a temporary attraction between the oxygen and hydrogen, because remember, oxygen has a partial negative charge while hydrogen has a partial positive charge. So that’s what hydrogen bonds are; they aren’t bonds in between the atoms, they’re bonds in between the actual different molecules. Not between the atoms. So that’s it for intermolecular forces.

0:10:54

0:10:54

0:05:19

0:05:19

0:10:40

0:10:40

0:08:07

0:08:07

0:08:05

0:08:05

0:08:36

0:08:36

0:05:37

0:05:37

0:55:46

0:55:46

0:11:03

0:11:03

0:15:56

0:15:56

0:07:01

0:07:01

0:11:41

0:11:41

0:35:58

0:35:58

0:22:03

0:22:03

0:07:59

0:07:59

0:21:14

0:21:14

0:05:20

0:05:20

0:05:20

0:05:20

0:21:25

0:21:25

0:01:19

0:01:19

0:14:17

0:14:17

0:47:35

0:47:35

0:11:17

0:11:17

0:10:46

0:10:46