filmov

tv

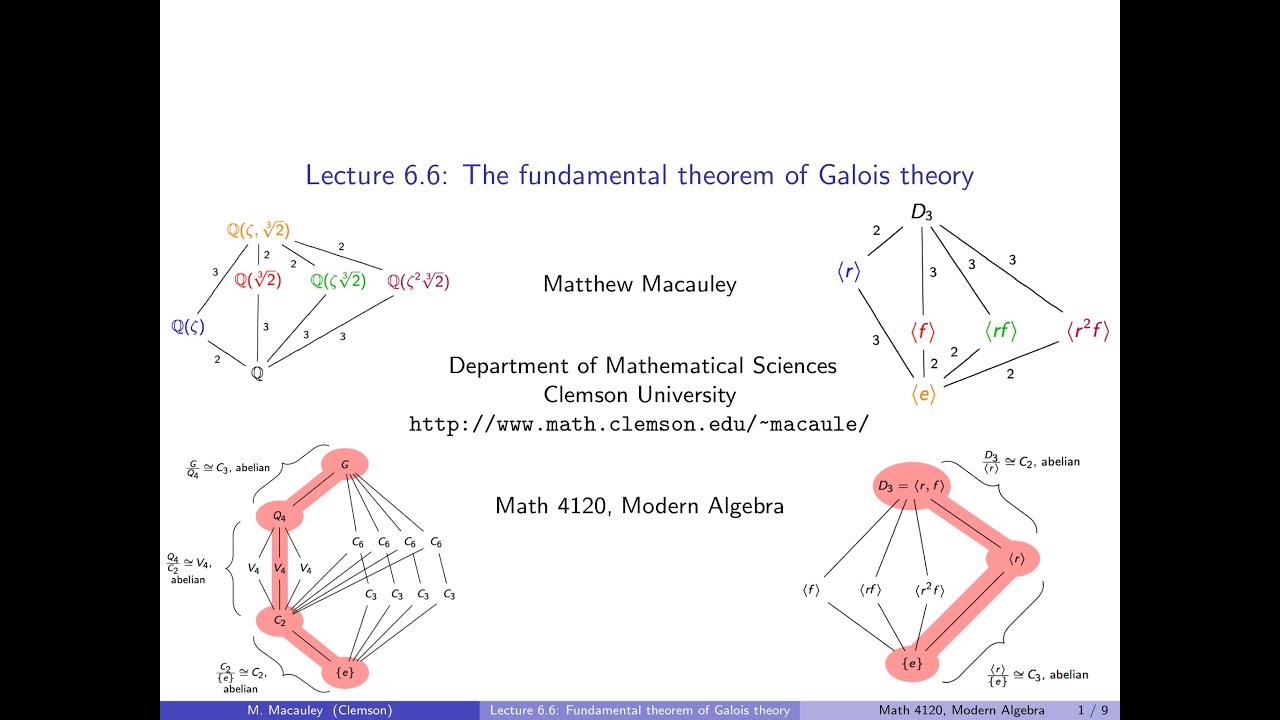

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.6: The fundamental theorem of Galois theory

Показать описание

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.6: The fundamental theorem of Galois theory

The fundamental theorem of Galois theory guarantees a remarkable correspondence between the subfield lattice of a polynomial and the subgroup lattice of its Galois group. After illustrating this with a detailed example, we define what it means for a group to be "solvable". Galois proved that a polynomial is solvable by radicals if and only if its Galois group is solvable. We conclude by finding a degree-5 polynomial f(x) whose Galois group acts on the roots by a 5-cycle and by a 2-cycle. Since these two elements generate the (unsolvable) symmetric group S_5, the roots of f(x) are unsolvable by radicals.

The fundamental theorem of Galois theory guarantees a remarkable correspondence between the subfield lattice of a polynomial and the subgroup lattice of its Galois group. After illustrating this with a detailed example, we define what it means for a group to be "solvable". Galois proved that a polynomial is solvable by radicals if and only if its Galois group is solvable. We conclude by finding a degree-5 polynomial f(x) whose Galois group acts on the roots by a 5-cycle and by a 2-cycle. Since these two elements generate the (unsolvable) symmetric group S_5, the roots of f(x) are unsolvable by radicals.

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.6: The fundamental theorem of Galois theory

Visual Group Theory: Lecture 7.5: Euclidean domains and algebraic integers

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.5: Galois group actions and normal field extensions

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.1: Fields and their extensions

Symmetric Groups (Abstract Algebra)

Lecture 6 Normal Extensions

Group theory 6: normal subgroups and quotient groups

Morphisms, rings, and fields | Group theory episode 6

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 4.6: Automorphisms

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 5.7: Finite simple groups

Group Theory, lecture 2.4: Conjugation in the symmetric group

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 2.1: Cyclic and abelian groups

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 5.3: Examples of group actions

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.4: Galois groups

Group Theory: Lecture 21/30 - Conjugacy Classes of the Alternating Group

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 2.3: Symmetric and alternating groups

The Group Theory Used to Solve the Hardest Differential Equation

Why study Lie theory? | Lie groups, algebras, brackets #1

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.2: Field automorphisms

Group Theory in Physics 6-A: Galois Theory -1 (in Persian)

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 6.7: Ruler and compass constructions

How small are atoms?

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 2.4: Cayley's theorem

Visual Group Theory, Lecture 3.2: Cosets

Комментарии

0:31:29

0:31:29

0:30:09

0:30:09

0:26:28

0:26:28

0:26:34

0:26:34

0:05:30

0:05:30

0:37:51

0:37:51

0:24:48

0:24:48

0:31:13

0:31:13

0:24:34

0:24:34

0:36:34

0:36:34

0:30:47

0:30:47

0:30:45

0:30:45

0:44:05

0:44:05

0:34:13

0:34:13

0:35:57

0:35:57

0:29:50

0:29:50

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:04:26

0:04:26

0:35:41

0:35:41

1:05:32

1:05:32

0:22:46

0:22:46

0:00:48

0:00:48

0:11:00

0:11:00

0:19:11

0:19:11