filmov

tv

WACC explained

Показать описание

Weighted Average Cost of Capital, in short WACC. This seems to be one of the most intimidating concepts in finance. Fear not, this video explains WACC in an easy to understand way. We will cover: what WACC means, how WACC is used, how WACC is calculated in the WACC formula, and why the WACC formula is pseudo-science, in other words: of questionable value and potentially dangerous. What does the acronym WACC stand for? The WACC is the Weighted Average Cost of Capital. Weighted Average indicates that we are going to apply some mathematics to get the proportions right, and Cost of Capital indicates an attempt to identify the cost of various types of capital. WACC is a calculation of a firm's cost of capital in which each category of capital is proportionately weighted. The #WACC is often used to try to answer the fundamental question in life for both investors and businesses: can we create value?

⏱️TIMESTAMPS⏱️

00:00 Introduction to WACC

00:30 WACC acronym

00:58 WACC and value creation

01:58 WACC and Free Cash Flow

03:31 WACC and enterprise value

05:06 Analyst stock recommendations

05:42 WACC and NPV

06:39 WACC formula

08:23 Cost of equity in WACC

09:13 WACC and CAPM

10:47 WACC/CAPM limitations

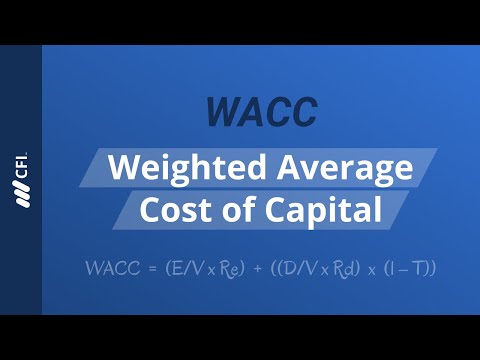

So how does the infamous formula work to calculate WACC? Here’s the simplest version of it, assuming just two classes of capital: debt and equity. Weighted Average Cost of Capital equals the market value of a firm’s debt divided by the market value of debt and equity, times the cost of debt, plus the market value of a firm’s equity divided by the market value of debt and equity, times the cost of equity. Remember the definition of Weighted Average Cost of Capital: a calculation of a firm's cost of capital in which each category of capital is proportionately weighted. So this thing about debt divided by debt plus equity, and equity divided by debt plus equity, takes care of getting the proportions weighted. The multiplication is with cost of debt in the first part, and cost of equity in the second part. Let’s illustrate this with a WACC example of a fictitious company. Debt is $250 million, out of total capital of $1 billion, so 25%. Cost of debt is 4%. Equity is $750 million, out of total capital of $1 billion, so 75%. Cost of equity is 16%. Multiply, and then add up, and you get to a Weighted Average Cost of Capital of 13%. So where does this cost of debt, and cost of equity, come from? The first part is fairly easy to grasp. The cost of debt equals the interest rate that the company pays on its interest-bearing debt, minus the tax benefit of interest expense being deductible. So if the interest rate is 5%, and the corporate tax rate 20%, then the after-tax cost of debt is 4%. Then comes the more challenging part: cost of equity. At this point, I hope you’ll say “what do you mean, cost of equity? Isn’t the whole idea that equity holds no legal obligation for the firm to pay anything?” No, says the economist, you should look at the opportunity cost of the equity capital. An investor doesn’t have to invest in this company if he doesn’t want to, he could earn a return elsewhere. Cost of equity is therefore a required return by shareholders for the risk they take by investing in this specific equity. And that’s where the whole idea goes off the rails, as we start using historical statistics to predict the future, basically fitting a line to past data hoping that this has any semblance to what the future might hold.

Philip de Vroe (The Finance Storyteller) aims to make strategy, #finance and leadership enjoyable and easier to understand. Learn the business and accounting vocabulary to join the conversation with your CEO at your company. Understand how financial statements work in order to make better investing decisions. Philip delivers #financetraining in various formats: YouTube videos, classroom sessions, webinars, and business simulations. Connect with me through Linked In!

⏱️TIMESTAMPS⏱️

00:00 Introduction to WACC

00:30 WACC acronym

00:58 WACC and value creation

01:58 WACC and Free Cash Flow

03:31 WACC and enterprise value

05:06 Analyst stock recommendations

05:42 WACC and NPV

06:39 WACC formula

08:23 Cost of equity in WACC

09:13 WACC and CAPM

10:47 WACC/CAPM limitations

So how does the infamous formula work to calculate WACC? Here’s the simplest version of it, assuming just two classes of capital: debt and equity. Weighted Average Cost of Capital equals the market value of a firm’s debt divided by the market value of debt and equity, times the cost of debt, plus the market value of a firm’s equity divided by the market value of debt and equity, times the cost of equity. Remember the definition of Weighted Average Cost of Capital: a calculation of a firm's cost of capital in which each category of capital is proportionately weighted. So this thing about debt divided by debt plus equity, and equity divided by debt plus equity, takes care of getting the proportions weighted. The multiplication is with cost of debt in the first part, and cost of equity in the second part. Let’s illustrate this with a WACC example of a fictitious company. Debt is $250 million, out of total capital of $1 billion, so 25%. Cost of debt is 4%. Equity is $750 million, out of total capital of $1 billion, so 75%. Cost of equity is 16%. Multiply, and then add up, and you get to a Weighted Average Cost of Capital of 13%. So where does this cost of debt, and cost of equity, come from? The first part is fairly easy to grasp. The cost of debt equals the interest rate that the company pays on its interest-bearing debt, minus the tax benefit of interest expense being deductible. So if the interest rate is 5%, and the corporate tax rate 20%, then the after-tax cost of debt is 4%. Then comes the more challenging part: cost of equity. At this point, I hope you’ll say “what do you mean, cost of equity? Isn’t the whole idea that equity holds no legal obligation for the firm to pay anything?” No, says the economist, you should look at the opportunity cost of the equity capital. An investor doesn’t have to invest in this company if he doesn’t want to, he could earn a return elsewhere. Cost of equity is therefore a required return by shareholders for the risk they take by investing in this specific equity. And that’s where the whole idea goes off the rails, as we start using historical statistics to predict the future, basically fitting a line to past data hoping that this has any semblance to what the future might hold.

Philip de Vroe (The Finance Storyteller) aims to make strategy, #finance and leadership enjoyable and easier to understand. Learn the business and accounting vocabulary to join the conversation with your CEO at your company. Understand how financial statements work in order to make better investing decisions. Philip delivers #financetraining in various formats: YouTube videos, classroom sessions, webinars, and business simulations. Connect with me through Linked In!

Комментарии

0:13:57

0:13:57

0:02:16

0:02:16

0:06:40

0:06:40

0:03:43

0:03:43

0:06:28

0:06:28

0:17:01

0:17:01

0:17:56

0:17:56

0:04:25

0:04:25

0:07:17

0:07:17

0:29:17

0:29:17

0:02:00

0:02:00

0:15:54

0:15:54

0:00:52

0:00:52

0:08:26

0:08:26

0:29:35

0:29:35

0:01:16

0:01:16

0:10:59

0:10:59

0:11:22

0:11:22

0:16:28

0:16:28

0:05:32

0:05:32

0:10:35

0:10:35

0:06:59

0:06:59

0:05:20

0:05:20

0:33:54

0:33:54