filmov

tv

The Failures of Property Dualism

Показать описание

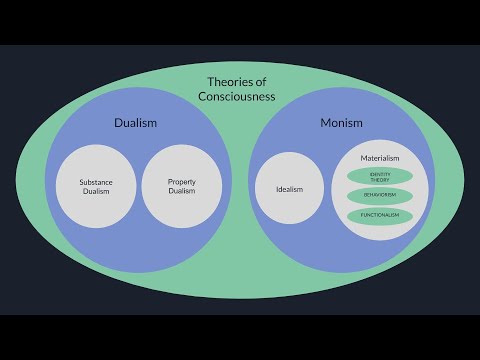

Why property dualism (non-reductive physicalism) fails to maintain mental causation, substance monism, and emergence.

Timestamps

00:00 – Introduction

00:24 – The Interaction Problem

02:24 – The Exclusion Problem

03:40 – A Lapse into Substance Dualism

06:52 – The Incoherence/Inexplicability of Strong Emergence

09:05 – Conclusion

Sources:

(The Interaction Problem)

Sally Latham – Property Dualism

Ralph Weir – Why Property Dualists Should be Cartesians

Elliot Goodine – Discussing Property Dualism

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Mental Causation – 4. Problem I: Property Dualism

William Lycan – Is Property Dualism Better Off than Substance Dualism?

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Mental Causation – 6.2 The Exclusion Problem

(A Lapse into Substance Dualism)

Susan Schneider – Non-Reductive Physicalism and the Mind Problem

Dean Zimmerman – From Property Dualism to Substance Dualism

John Searle – Why I Am Not a Property Dualist

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Emergent Properties – 4.3 Strong emergence: from property to substance dualism?

(The Incoherence/Inexplicability of Strong Emergence)

Godehard Brüntrup – What is Panpsychism?

William Seager – Panpsychism vs. Strong Emergence?

Mark Bedau – Weak Emergence

(Conclusion)

Jaegwon Kim – The Myth of Non-Reductive Materialism

Music Credits:

SilverHawk – Girls of Summer

SilverHawk – Pumping Iron

Movie Credits:

Casper (1995)

Ghost (1990)

The Mask (1994)

#dualism #materialism #emergence #strongemergence #reductionism #physicalism #propertydualism

"Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for "fair use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use."

Timestamps

00:00 – Introduction

00:24 – The Interaction Problem

02:24 – The Exclusion Problem

03:40 – A Lapse into Substance Dualism

06:52 – The Incoherence/Inexplicability of Strong Emergence

09:05 – Conclusion

Sources:

(The Interaction Problem)

Sally Latham – Property Dualism

Ralph Weir – Why Property Dualists Should be Cartesians

Elliot Goodine – Discussing Property Dualism

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Mental Causation – 4. Problem I: Property Dualism

William Lycan – Is Property Dualism Better Off than Substance Dualism?

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Mental Causation – 6.2 The Exclusion Problem

(A Lapse into Substance Dualism)

Susan Schneider – Non-Reductive Physicalism and the Mind Problem

Dean Zimmerman – From Property Dualism to Substance Dualism

John Searle – Why I Am Not a Property Dualist

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Emergent Properties – 4.3 Strong emergence: from property to substance dualism?

(The Incoherence/Inexplicability of Strong Emergence)

Godehard Brüntrup – What is Panpsychism?

William Seager – Panpsychism vs. Strong Emergence?

Mark Bedau – Weak Emergence

(Conclusion)

Jaegwon Kim – The Myth of Non-Reductive Materialism

Music Credits:

SilverHawk – Girls of Summer

SilverHawk – Pumping Iron

Movie Credits:

Casper (1995)

Ghost (1990)

The Mask (1994)

#dualism #materialism #emergence #strongemergence #reductionism #physicalism #propertydualism

"Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for "fair use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use."

Комментарии

0:10:01

0:10:01

0:06:44

0:06:44

0:05:50

0:05:50

0:02:58

0:02:58

0:16:51

0:16:51

1:20:14

1:20:14

0:10:09

0:10:09

0:20:44

0:20:44

0:28:55

0:28:55

1:57:59

1:57:59

0:12:23

0:12:23

0:10:29

0:10:29

1:10:30

1:10:30

0:09:56

0:09:56

1:17:20

1:17:20

0:59:36

0:59:36

0:21:44

0:21:44

0:47:14

0:47:14

0:49:20

0:49:20

1:15:45

1:15:45

0:29:52

0:29:52

0:00:49

0:00:49

0:50:05

0:50:05

0:18:26

0:18:26