filmov

tv

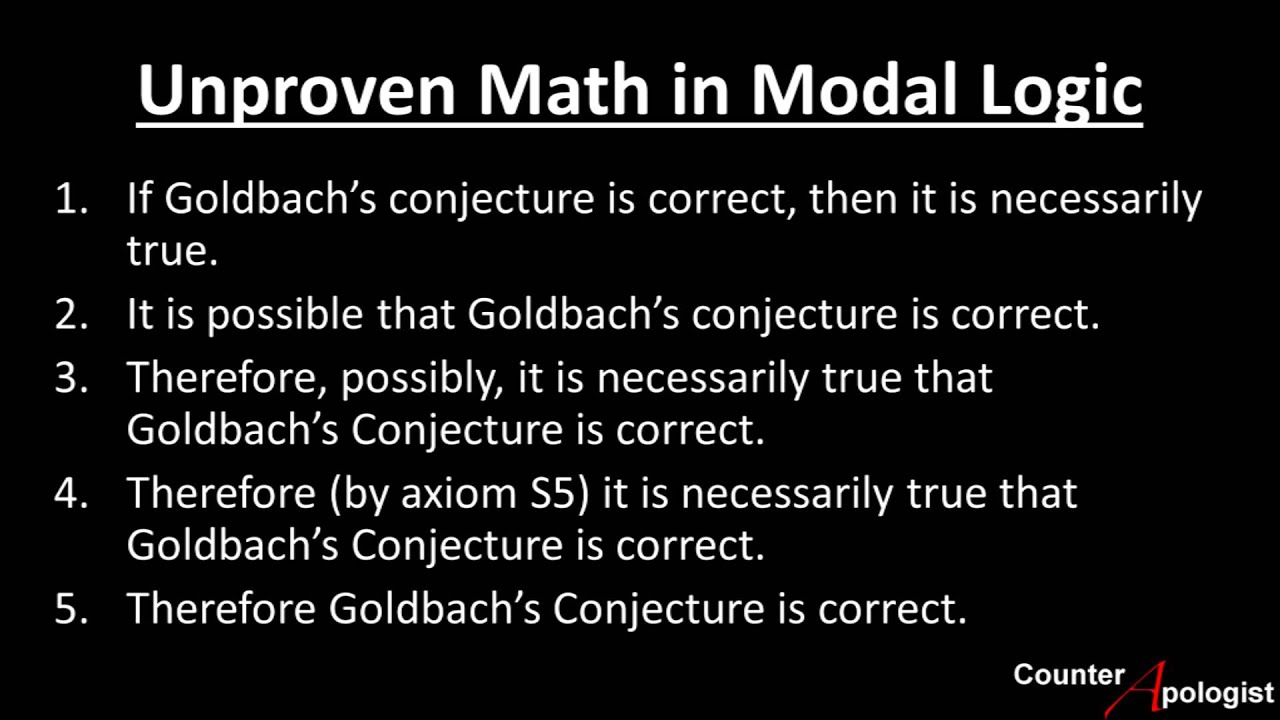

Countering the Modal Ontological Argument

Показать описание

References:

Countering the Modal Ontological Argument

'I Think, Therefore God Exists' | The Ontological Argument (AFG #5)

Modal Ontological Argument By Rationality Rules

Why the Ontological Argument Sucks

Everything Wrong with the Modal Ontological Argument

Is the Ontological Argument the Worst?

Refuting the Ontological Argument

Matt Dillahunty on Anselm's Ontological Argument

The Ontological Argument (Argument for the Existence of God)

A User's Guide to the Modal Ontological Argument

Anselm & the Argument for God: Crash Course Philosophy #9

Refining the Modal Ontological Argument - Animating Rebel

Criticisms of the Ontological Argument

Stephen Colbert on St Anslem's Ontological Argument

The Arguments for God's Existence Tier List

'God's Perfect Logic Trap?' - Debunking the Modal Ontological Argument

ATHEISTS BEWARE: Oncoming Strategy from Christian Apologists (Modal Ontological Argument)

Every Argument for God DEBUNKED!

Betting on Necessity: The Modal Ontological Argument

The Ontological Argument

Kant's Criticism of the Ontological Argument

Understanding the Ontological Argument

Refuting William Lane Craig's Ontological Argument

The most OP argument for (defending) God

Комментарии

0:12:27

0:12:27

0:13:31

0:13:31

0:00:46

0:00:46

0:08:30

0:08:30

0:20:48

0:20:48

0:03:23

0:03:23

0:02:55

0:02:55

0:01:44

0:01:44

0:06:55

0:06:55

1:23:12

1:23:12

0:09:13

0:09:13

0:02:02

0:02:02

0:10:29

0:10:29

0:00:33

0:00:33

0:17:10

0:17:10

0:08:11

0:08:11

0:04:58

0:04:58

0:15:38

0:15:38

0:34:01

0:34:01

0:12:35

0:12:35

0:02:10

0:02:10

0:07:13

0:07:13

0:03:02

0:03:02

0:11:59

0:11:59