filmov

tv

Logic at its Limit: The Grelling-Nelson Paradox

Показать описание

Whoever said logic was infallible? Certainly not the German logicians who, in 1908, discovered this mind-bending paradox. Learn how they beat reason at its own game, all by asking a single question about two simple words. Don't skimp out or you'll miss the surprise twist at the end! Plus: a very brief, totally not copyright-infringing appearance by The Sorting Hat.

Contents:

00:00 - A Tale of Two Words

02:04 - Semantic Sorting

03:30 - Paradox in a Nutshell

04:41 - Grammatical Formulas

06:53 - Breaking Logic

10:12 - The Naive Objection

11:18 - This was never about words, was it?

Contents:

00:00 - A Tale of Two Words

02:04 - Semantic Sorting

03:30 - Paradox in a Nutshell

04:41 - Grammatical Formulas

06:53 - Breaking Logic

10:12 - The Naive Objection

11:18 - This was never about words, was it?

Logic at its Limit: The Grelling-Nelson Paradox

The Limits of Logic

Woke Feminist Gets OWNED By Basic Logic on Gender

Best Riddles That'll Challenge Your Logic To Its Limit

Limits of Logic: The Gödel Legacy

Understanding Logic vs Emotion - The Limits Of Rationality

The Language of Predicate Logic (The Power and Limits of Logic, 1a)

geometry dash logic

10 Best Riddles That'll Challenge Your Logic To Its Limit 🤓

Models, and Soundness for Predicate Logic (The Power and Limits of Logic, 2)

Based Woman DEBUNKS Woke Feminist's Logic On What A Woman Is During Piers Morgan Show

What are the limits of logic? | Shahidha Bari, Iain McGilchrist, Beatrix Campbell, Simon Blackburn

Countability and Diagonalisation (The Power and Limits of Logic, 5)

YAHOO Interview Puzzle || Camel and Bananas || Logic + Optimization

Completeness for Predicate Logic (The Power and Limits of Logic, 3)

Ben Shapiro Breaks AI Chatbot (with Facts & Logic)

Romans 14 | October 2024 | Morning Koinonia | Pastor Flourish Peters | The LOGIC Church

Proofs for Predicate Logic (The Power and Limits of Logic, 1b)

Airbag Deployment Logic #shorts

Circular Reasoning: The Never-Ending Loop of Logic

Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! - ABBA // Synth Cover (Novation Launchkey & Logic Pro X)

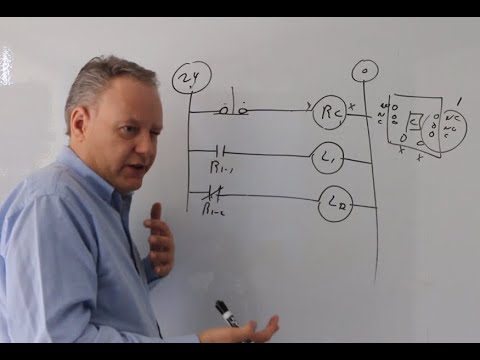

Introduction to Ladder Logic with Relays

Non-Recursive Functions (The Power and Limits of Logic, 9)

Diagonalisation and its Consequences (The Power and Limits of Logic, 11)

Комментарии

0:13:35

0:13:35

0:21:11

0:21:11

0:00:26

0:00:26

0:19:02

0:19:02

0:58:16

0:58:16

0:08:54

0:08:54

0:41:10

0:41:10

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:13:55

0:13:55

0:34:57

0:34:57

0:00:37

0:00:37

0:10:09

0:10:09

0:16:29

0:16:29

0:05:34

0:05:34

0:43:11

0:43:11

0:15:37

0:15:37

0:34:44

0:34:44

0:29:44

0:29:44

0:00:30

0:00:30

0:00:29

0:00:29

0:00:58

0:00:58

0:05:33

0:05:33

0:30:48

0:30:48

0:31:24

0:31:24