filmov

tv

Is There a Mathematical Model of the Mind? (Panel Discussion)

Показать описание

A Google TechTalk, presented by Bin Yu, Geoffrey Hinton, Jack Gallant, Lenore Blum, Percy Liang, Rina Panigrahy, 2021/05/17

The panelists:

Bin Yu - UC Berkeley

Geoffrey Hinton - University of Toronto and Google

Jack Gallant - UC Berkeley

Lenore Blum - CMU/UC Berkeley

Percy Liang - Stanford University

Rina Panigrahy - Google (moderator)

The panelists:

Bin Yu - UC Berkeley

Geoffrey Hinton - University of Toronto and Google

Jack Gallant - UC Berkeley

Lenore Blum - CMU/UC Berkeley

Percy Liang - Stanford University

Rina Panigrahy - Google (moderator)

Is There a Mathematical Model of the Mind? (Panel Discussion)

What is a (mathematical) model?

Mathematical Models

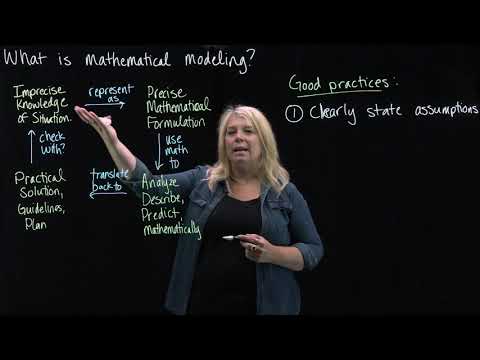

What is Mathematical Modeling?

What is Math Modeling? Video Series Part 1: What is Math Modeling?

How To Create A Mathematical Model?

Mathematical Modeling and Variation Ft. The Math Sorcerer

How to use a mathematical model like a compass #science #maths

MATLAB TUTORIAL | Solving Ordinary Differential Equations in MATLAB.

Mathematical Models in Real Time Application

Lecture 1: Basics of Mathematical Modeling

MECHANICS: What is Mathematical Modeling?

Introduction to Mathematical Models - Functional Relationships I (Module 2 1 1)

The Problem of Traffic: A Mathematical Modeling Journey

Can One Mathematical Model Explain All Patterns In Nature?

Common Mathematical models in Physics

Mathematical model of Coronavirus spread in USA.

Maths working model, addition, subtraction, multiplication, division

Mathematical Modeling Simplified

Mathematical Models and Understanding Infectious Disease with Dr. Necibe Tuncer

Mathematical model of car's velocity and acceleration

Teaching Mathematical Modelling - A new framework

Blending Mathematical Models with Data: Andrew Stuart Shares Real-World Examples

Fraction working model school project| school project fraction|

Комментарии

0:55:35

0:55:35

0:03:45

0:03:45

0:01:22

0:01:22

0:11:03

0:11:03

0:03:13

0:03:13

0:37:20

0:37:20

0:04:38

0:04:38

0:00:40

0:00:40

0:06:34

0:06:34

1:10:54

1:10:54

0:25:44

0:25:44

0:06:41

0:06:41

0:08:05

0:08:05

0:34:09

0:34:09

0:04:13

0:04:13

0:10:57

0:10:57

0:21:06

0:21:06

0:00:16

0:00:16

0:02:12

0:02:12

0:00:36

0:00:36

0:03:48

0:03:48

0:32:28

0:32:28

0:01:08

0:01:08

0:00:33

0:00:33