filmov

tv

Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics

Показать описание

The measurement problem

Other places you can find content from me:

Patreon - authortomharper

Blog - The Cynical Philosopher

Twitter - @AuthorTomHarper

Amazon - Author Profile

My science fiction series available on Amazon

Incarnate: Existence

Incarnate: Essence

Incarnate: Schism

Other places you can find content from me:

Patreon - authortomharper

Blog - The Cynical Philosopher

Twitter - @AuthorTomHarper

Amazon - Author Profile

My science fiction series available on Amazon

Incarnate: Existence

Incarnate: Essence

Incarnate: Schism

The Problem with Quantum Measurement

The measurement problem in quantum mechanics with physicist Sean Carroll and Joe Rogan

What is the quantum measurement problem?

'The measurement problem violates the Schrödinger equation' | Roger Penrose on #quantummec...

Sean Carroll explains: what is the measurement problem in quantum mechanics?

The Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics: A Discussion of Interpretations and Experiments

David Albert: The Measurement Problem of Quantum Mechanics

Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics #physics

John Martinis: Quantum Systems Engineering

What’s the measurement problem in quantum mechanics?

Chaos: The real problem with quantum mechanics

What is the Measurement Problem of Quantum Mechanics? | David Albert

Part 1: Solution To The Measurement Problem

Why Quantum Mechanics Is an Inconsistent Theory | Roger Penrose & Jordan Peterson

Quantum Interactions and the Measurement Problem - Joe Rogan #shorts #joerogan #jre

The Measurement Problem in Quantum Physics: Reality vs. Observation!

Understanding Quantum Mechanics #5: Decoherence

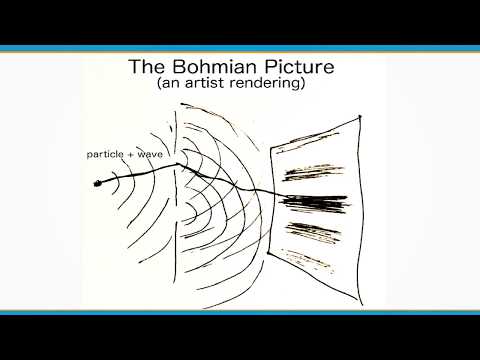

The Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics & Bohmian Mechanics

What is Quantum Mechanics Really Trying to Tell us about Reality? Featuring @SabineHossenfelder

Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics

the measurement problem of quantum mechanics

Unbelievable Truth About Quantum Mechanics Measurement Problem Uncovered #watchwhenbored #shorts

Sean Carroll on the Measurement Problem and Quantum Field Theory

Joe Rogan on what is Quantum Measurement #joerogan #podcast

Комментарии

0:06:57

0:06:57

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:00:44

0:00:44

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:02:54

0:02:54

0:08:49

0:08:49

2:03:14

2:03:14

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:58:56

0:58:56

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:11:44

0:11:44

0:11:08

0:11:08

0:27:28

0:27:28

0:06:34

0:06:34

0:00:48

0:00:48

0:00:49

0:00:49

0:12:32

0:12:32

0:05:46

0:05:46

0:19:49

0:19:49

0:04:42

0:04:42

0:00:28

0:00:28

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:02:02

0:02:02

0:00:14

0:00:14