filmov

tv

NASA Confirms 5,000 Exoplanets. New Giant Space Telescopes Are Coming.

Показать описание

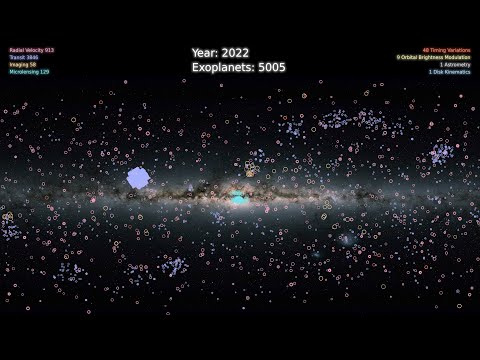

The count of confirmed exoplanets just ticked past the 5,000 mark, representing a 30-year journey of discovery led by NASA space telescopes.

Not so long ago, we lived in a universe with only a small number of known planets, all of them orbiting our Sun. But a new raft of discoveries marks a scientific high point: More than 5,000 planets are now confirmed to exist beyond our solar system.

The planetary odometer turned on March 21, with the latest batch of 65 exoplanets – planets outside our immediate solar family – added to the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The archive records exoplanet discoveries that appear in peer-reviewed, scientific papers, and that have been confirmed using multiple detection methods or by analytical techniques.

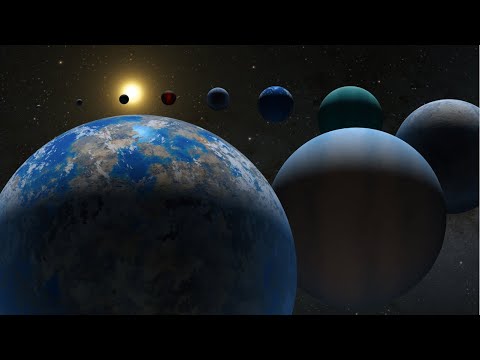

The 5,000-plus planets found so far include small, rocky worlds like Earth, gas giants many times larger than Jupiter, and “hot Jupiters” in scorchingly close orbits around their stars. There are “super-Earths,” which are possible rocky worlds bigger than our own, and “mini-Neptunes,” smaller versions of our system’s Neptune. Add to the mix planets orbiting two stars at once and planets stubbornly orbiting the collapsed remnants of dead stars.

We do know this: Our galaxy likely holds hundreds of billions of such planets. The steady drumbeat of discovery began in 1992 with strange new worlds orbiting an even stranger star. It was a type of neutron star known as a pulsar, a rapidly spinning stellar corpse that pulses with millisecond bursts of searing radiation. Measuring slight changes in the timing of the pulses allowed scientists to reveal planets in orbit around the pulsar.

Finding just three planets around this spinning star essentially opened the floodgates, said Alexander Wolszczan, the lead author on the paper that, 30 years ago, unveiled the first planets to be confirmed outside our solar system.

Wolszczan, who still searches for exoplanets as a professor at Penn State, says we’re opening an era of discovery that will go beyond simply adding new planets to the list. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in 2018, continues to make new exoplanet discoveries. But soon powerful next-generation telescopes and their highly sensitive instruments, starting with the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, will capture light from the atmospheres of exoplanets, reading which gases are present to potentially identify tell-tale signs of habitable conditions.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, expected to launch in 2027, will make new exoplanet discoveries using a variety of methods. The ESA (European Space Agency) mission ARIEL, launching in 2029, will observe exoplanet atmospheres; a piece of NASA technology aboard, called CASE, will help zero in on exoplanet clouds and hazes.

How to Find Other Worlds

The picture didn’t always look so bright. The first planet detected around a Sun-like star, in 1995, turned out to be a hot Jupiter: a gas giant about half the mass of our own Jupiter in an extremely close, four-day orbit around its star. A year on this planet, in other words, lasts only four days.

More such planets appeared in the data from ground-based telescopes once astronomers learned to recognize them – first dozens, then hundreds. They were found using the “wobble” method: tracking slight back-and-forth motions of a star, caused by gravitational tugs from orbiting planets. But still, nothing looked likely to be habitable.

Finding small, rocky worlds more like our own required the next big leap in exoplanet-hunting technology: the “transit” method.

That idea was realised in the Kepler Space Telescope.

A team of scientists found NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will be able to measure a specific kind of space dust littered throughout dozens of nearby planetary systems’ habitable zones, or the regions around stars where temperatures are mild enough that liquid water could pool on worlds’ surfaces. Finding out how much of this material these systems contain would help astronomers learn more about how rocky planets form and guide the search for habitable worlds by future missions.

In our own solar system, zodiacal dust – small rocky grains largely left behind by colliding asteroids and crumbling comets – spans from near the Sun to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Seen from a distance, it’s the brightest thing in the solar system after the Sun. In other planetary systems it’s called exozodiacal dust and creates a haze that obscures our view of planets because it scatters light from the host star.

Chris Smith (KBRwyle): Lead Producer

Chris Smith (KBRwyle): Lead Animator

Jeanette Kazmierczak (University of Maryland College Park): Lead Science Writer

Christina Hedges (BAERI/Ames): Lead Scientist

Not so long ago, we lived in a universe with only a small number of known planets, all of them orbiting our Sun. But a new raft of discoveries marks a scientific high point: More than 5,000 planets are now confirmed to exist beyond our solar system.

The planetary odometer turned on March 21, with the latest batch of 65 exoplanets – planets outside our immediate solar family – added to the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The archive records exoplanet discoveries that appear in peer-reviewed, scientific papers, and that have been confirmed using multiple detection methods or by analytical techniques.

The 5,000-plus planets found so far include small, rocky worlds like Earth, gas giants many times larger than Jupiter, and “hot Jupiters” in scorchingly close orbits around their stars. There are “super-Earths,” which are possible rocky worlds bigger than our own, and “mini-Neptunes,” smaller versions of our system’s Neptune. Add to the mix planets orbiting two stars at once and planets stubbornly orbiting the collapsed remnants of dead stars.

We do know this: Our galaxy likely holds hundreds of billions of such planets. The steady drumbeat of discovery began in 1992 with strange new worlds orbiting an even stranger star. It was a type of neutron star known as a pulsar, a rapidly spinning stellar corpse that pulses with millisecond bursts of searing radiation. Measuring slight changes in the timing of the pulses allowed scientists to reveal planets in orbit around the pulsar.

Finding just three planets around this spinning star essentially opened the floodgates, said Alexander Wolszczan, the lead author on the paper that, 30 years ago, unveiled the first planets to be confirmed outside our solar system.

Wolszczan, who still searches for exoplanets as a professor at Penn State, says we’re opening an era of discovery that will go beyond simply adding new planets to the list. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in 2018, continues to make new exoplanet discoveries. But soon powerful next-generation telescopes and their highly sensitive instruments, starting with the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, will capture light from the atmospheres of exoplanets, reading which gases are present to potentially identify tell-tale signs of habitable conditions.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, expected to launch in 2027, will make new exoplanet discoveries using a variety of methods. The ESA (European Space Agency) mission ARIEL, launching in 2029, will observe exoplanet atmospheres; a piece of NASA technology aboard, called CASE, will help zero in on exoplanet clouds and hazes.

How to Find Other Worlds

The picture didn’t always look so bright. The first planet detected around a Sun-like star, in 1995, turned out to be a hot Jupiter: a gas giant about half the mass of our own Jupiter in an extremely close, four-day orbit around its star. A year on this planet, in other words, lasts only four days.

More such planets appeared in the data from ground-based telescopes once astronomers learned to recognize them – first dozens, then hundreds. They were found using the “wobble” method: tracking slight back-and-forth motions of a star, caused by gravitational tugs from orbiting planets. But still, nothing looked likely to be habitable.

Finding small, rocky worlds more like our own required the next big leap in exoplanet-hunting technology: the “transit” method.

That idea was realised in the Kepler Space Telescope.

A team of scientists found NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will be able to measure a specific kind of space dust littered throughout dozens of nearby planetary systems’ habitable zones, or the regions around stars where temperatures are mild enough that liquid water could pool on worlds’ surfaces. Finding out how much of this material these systems contain would help astronomers learn more about how rocky planets form and guide the search for habitable worlds by future missions.

In our own solar system, zodiacal dust – small rocky grains largely left behind by colliding asteroids and crumbling comets – spans from near the Sun to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Seen from a distance, it’s the brightest thing in the solar system after the Sun. In other planetary systems it’s called exozodiacal dust and creates a haze that obscures our view of planets because it scatters light from the host star.

Chris Smith (KBRwyle): Lead Producer

Chris Smith (KBRwyle): Lead Animator

Jeanette Kazmierczak (University of Maryland College Park): Lead Science Writer

Christina Hedges (BAERI/Ames): Lead Scientist

0:05:24

0:05:24

0:06:32

0:06:32

0:01:18

0:01:18

0:01:28

0:01:28

0:11:50

0:11:50

0:08:16

0:08:16

0:01:36

0:01:36

0:00:29

0:00:29

0:05:57

0:05:57

0:07:19

0:07:19

0:03:01

0:03:01

0:05:05

0:05:05

0:10:26

0:10:26

0:02:43

0:02:43

0:00:13

0:00:13

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:04:39

0:04:39

0:11:01

0:11:01

0:00:59

0:00:59

0:01:36

0:01:36

0:06:50

0:06:50

0:01:17

0:01:17

0:01:36

0:01:36

0:07:10

0:07:10