filmov

tv

How quantum mechanics requires non-additive measures

Показать описание

This video shows how a quantum analogue of the count of states must be non-additive: the total number of states is not necessarily the sum of disjoint subsets. The non-additivity appears because of contextuality: not all states are counted at all-else-being-equal. Quantization can be understood as imposing a count of states that is finite on finite continuous sets and is unitary on each single state.

The ideas presented are based on the following paper:

The ideas presented are based on the following paper:

How quantum mechanics requires non-additive measures

Non-additive (fuzzy) measure in quantum mechanics

Nicolò Defenu: Entanglement propagation and dynamics in non-additive quantum systems

Vikesh Siddhu on Non-additivity in quantum communication theory

Classical Algorithms for Quantum Mean Values

Graeme Smith - Additivity in classical and quantum Shannon theory

Day in My Life as a Quantum Computing Engineer!

Graeme Smith: Additivity in Classical and Quantum Shannon Theory

Theory of Quantum Channels From Bosonic Modes to Single Photons (Level 4)

GAME OVER!? - A.I. Designs New ELECTRIC Motor

Wave Functions in Quantum Mechanics: The SIMPLE Explanation | Quantum Mechanics... But Quickly

Why Classical Mechanics Fails (Quantum Essentials)

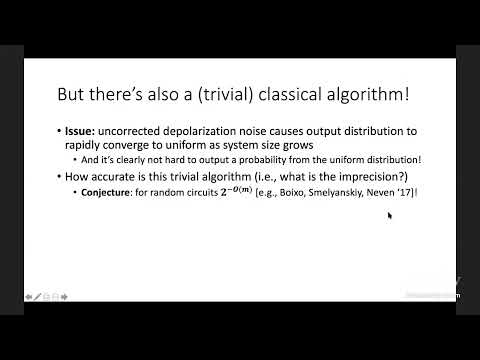

Noise vs Imprecision in the Hardness of Random Quantum Circuits

Non-Markovianity as a resource for quantum technologies

Michael Beverland (Microsoft) - Lower bounds on the non-Clifford resources for quantum computations

The equivalence between geometrical structures and entropy

Oliver Reardon-Smith: Resource theory based simulation of quantum circuits

Quantum differentiation and integration for the quantum plane

QIP 2021 | Leaking information to gain entanglement via log-singularities (Vikesh Siddhu)

Adam Burchardt: Thirty-six entangled officers of Euler

On the Principles of Differentiable Quantum Programming Languages

Grzegorz Rajchel Mieldzioc -- 36 entangled officers of Euler and quantum error correction codes

A Combinatorial Approach to Complexity Transitions in Quantum Physics

From One-shot to Asymptotic Quantum Information Theory - Marco Tomamichel - 3/5/2022

Комментарии

1:02:04

1:02:04

0:46:39

0:46:39

0:56:59

0:56:59

0:54:48

0:54:48

0:30:20

0:30:20

0:34:58

0:34:58

0:00:46

0:00:46

0:40:28

0:40:28

3:07:10

3:07:10

0:06:03

0:06:03

0:09:29

0:09:29

0:18:15

0:18:15

0:44:41

0:44:41

1:06:32

1:06:32

0:46:17

0:46:17

0:29:34

0:29:34

1:03:37

1:03:37

0:46:18

0:46:18

0:31:02

0:31:02

1:19:44

1:19:44

0:16:25

0:16:25

0:13:15

0:13:15

0:36:19

0:36:19

2:51:53

2:51:53