filmov

tv

PHILOSOPHY - Probability: The Monty Hall Problem [HD]

Показать описание

The Monty Hall problem is a strange result arising from a very simple situation. In this video, Bryce Gessell (Duke University) explains why it seems so counterintuitive and why the solution isn't counterintuitive at all.

Help us caption & translate this video!

Help us caption & translate this video!

PHILOSOPHY - Probability: The Monty Hall Problem [HD]

The Monty Hall Problem - Explained

The Monty Hall Problem: Switch Doors or Not?

Game Theory Scene | 21(2008) | Now Playing

Conditional probability - Monty Hall problem

The Monty Hall Problem

The Most Controversial Problem in Philosophy

Probability and the Monty Hall problem | Probability and combinatorics | Precalculus | Khan Academy

What is the 'Monty Hall' paradox problem in probability? (original explanation)

The Illusion of Probability - Monty Hall Paradox #VeritasiumContest

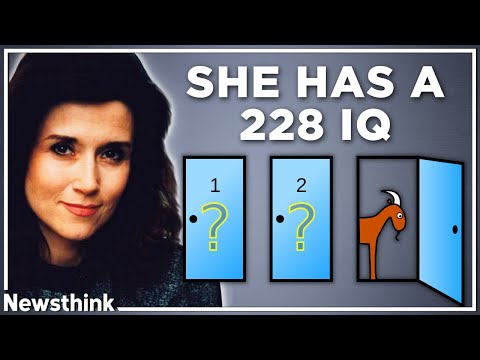

The Simple Question that Stumped Everyone Except Marilyn vos Savant

4.2.7 Monty Hall Problem: Video

Let’s Rethink the Monty Hall Problem

MontyHall Tree Diagram

The Monty Hall Problem -- Brain Teaser -- Probability Puzzle

Can you beat the Monty Hall problem?

What is the 'Monty Hall' paradox problem in probability? (alternative explanation)

What is Chance? - Probability | WIRELESS PHILOSOPHY

Monty Hall Problem Explained With Tree Diagram

The Simple Question That Stumps Everyone

Bertrand's Paradox - Probability | WIRELESS PHILOSOPHY

Proving The Monty Hall Problem

Can you solve the wizard standoff riddle? - Dan Finkel

Monty Hall Problem

Комментарии

0:04:17

0:04:17

0:02:48

0:02:48

0:00:50

0:00:50

0:03:39

0:03:39

0:06:08

0:06:08

0:15:59

0:15:59

0:10:19

0:10:19

0:07:23

0:07:23

0:04:57

0:04:57

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:07:06

0:07:06

0:08:42

0:08:42

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:00:14

0:00:14

0:06:49

0:06:49

0:00:37

0:00:37

0:03:57

0:03:57

0:07:28

0:07:28

0:04:41

0:04:41

0:00:58

0:00:58

0:07:44

0:07:44

0:03:33

0:03:33

0:05:26

0:05:26

0:01:21

0:01:21