filmov

tv

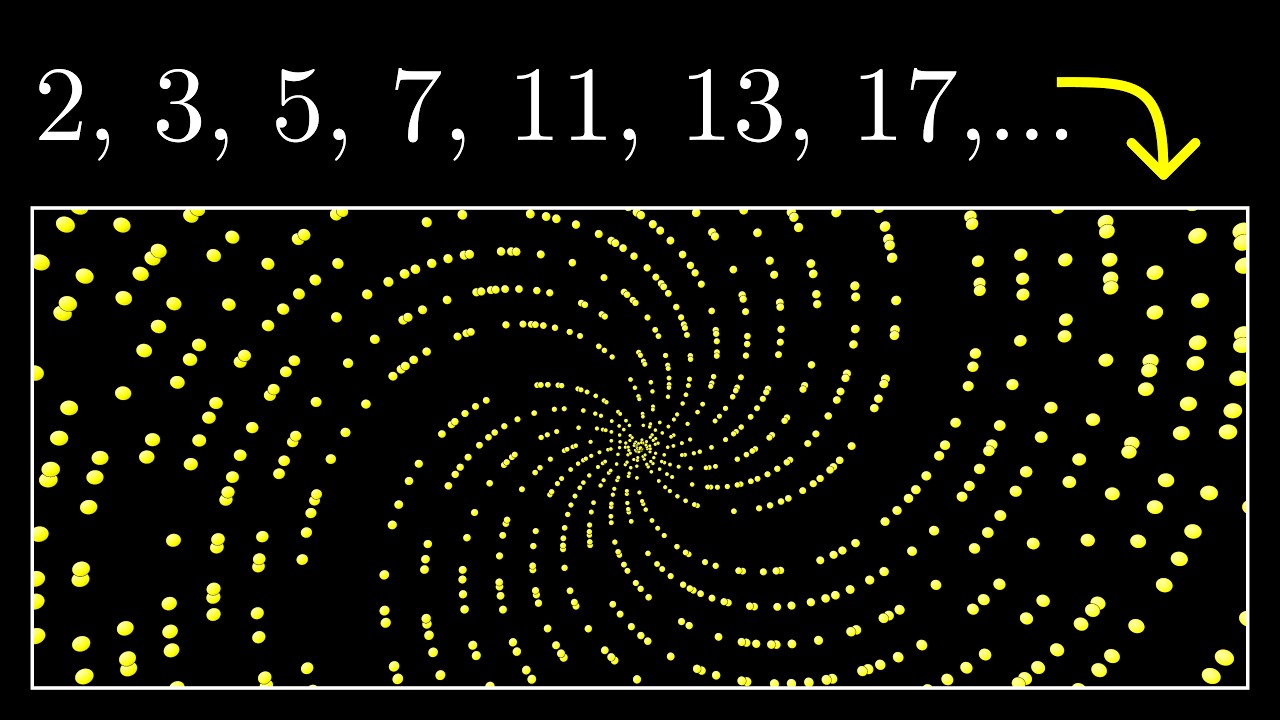

Why do prime numbers make these spirals? | Dirichlet’s theorem and pi approximations

Показать описание

A curious pattern, approximations for pi, and prime distributions.

An equally valuable form of support is to simply share some of the videos.

Based on this Math Stack Exchange post:

Want to learn more about rational approximations? See this Mathologer video.

Also, if you haven't heard of Ulam Spirals, you may enjoy this Numberphile video:

Dirichlet's paper:

Timestamps:

0:00 - The spiral mystery

3:35 - Non-prime spirals

6:10 - Residue classes

7:20 - Why the galactic spirals

9:30 - Euler’s totient function

10:28 - The larger scale

14:45 - Dirichlet’s theorem

20:26 - Why care?

Corrections:

18:30: In the video, I say that Dirichlet showed that the primes are equally distributed among allowable residue classes, but this is not historically accurate. (By "allowable", here, I mean a residue class whose elements are coprime to the modulus, as described in the video). What he actually showed is that the sum of the reciprocals of all primes in a given allowable residue class diverges, which proves that there are infinitely many primes in such a sequence.

Dirichlet observed this equal distribution numerically and noted this in his paper, but it wasn't until decades later that this fact was properly proved, as it required building on some of the work of Riemann in his famous 1859 paper. If I'm not mistaken, I think it wasn't until Vallée Poussin in (1899), with a version of the prime number theorem for residue classes like this, but I could be wrong there.

In many ways, this was a very silly error for me to have let through. It is true that this result was proven with heavy use of complex analysis, and in fact, it's in a complex analysis lecture that I remember first learning about it. But of course, this would have to have happened after Dirichlet because it would have to have happened after Riemann!

My apologies for the mistake. If you notice factual errors in videos that are not already mentioned in the video's description or pinned comment, don't hesitate to let me know.

Thanks to these viewers for their contributions to translations

Hebrew: Omer Tuchfeld

------------------

If you want to check it out, I feel compelled to warn you that it's not the most well-documented tool, and it has many other quirks you might expect in a library someone wrote with only their own use in mind.

Music by Vincent Rubinetti.

Download the music on Bandcamp:

Stream the music on Spotify:

If you want to contribute translated subtitles or to help review those that have already been made by others and need approval, you can click the gear icon in the video and go to subtitles/cc, then "add subtitles/cc". I really appreciate those who do this, as it helps make the lessons accessible to more people.

------------------

Various social media stuffs:

An equally valuable form of support is to simply share some of the videos.

Based on this Math Stack Exchange post:

Want to learn more about rational approximations? See this Mathologer video.

Also, if you haven't heard of Ulam Spirals, you may enjoy this Numberphile video:

Dirichlet's paper:

Timestamps:

0:00 - The spiral mystery

3:35 - Non-prime spirals

6:10 - Residue classes

7:20 - Why the galactic spirals

9:30 - Euler’s totient function

10:28 - The larger scale

14:45 - Dirichlet’s theorem

20:26 - Why care?

Corrections:

18:30: In the video, I say that Dirichlet showed that the primes are equally distributed among allowable residue classes, but this is not historically accurate. (By "allowable", here, I mean a residue class whose elements are coprime to the modulus, as described in the video). What he actually showed is that the sum of the reciprocals of all primes in a given allowable residue class diverges, which proves that there are infinitely many primes in such a sequence.

Dirichlet observed this equal distribution numerically and noted this in his paper, but it wasn't until decades later that this fact was properly proved, as it required building on some of the work of Riemann in his famous 1859 paper. If I'm not mistaken, I think it wasn't until Vallée Poussin in (1899), with a version of the prime number theorem for residue classes like this, but I could be wrong there.

In many ways, this was a very silly error for me to have let through. It is true that this result was proven with heavy use of complex analysis, and in fact, it's in a complex analysis lecture that I remember first learning about it. But of course, this would have to have happened after Dirichlet because it would have to have happened after Riemann!

My apologies for the mistake. If you notice factual errors in videos that are not already mentioned in the video's description or pinned comment, don't hesitate to let me know.

Thanks to these viewers for their contributions to translations

Hebrew: Omer Tuchfeld

------------------

If you want to check it out, I feel compelled to warn you that it's not the most well-documented tool, and it has many other quirks you might expect in a library someone wrote with only their own use in mind.

Music by Vincent Rubinetti.

Download the music on Bandcamp:

Stream the music on Spotify:

If you want to contribute translated subtitles or to help review those that have already been made by others and need approval, you can click the gear icon in the video and go to subtitles/cc, then "add subtitles/cc". I really appreciate those who do this, as it helps make the lessons accessible to more people.

------------------

Various social media stuffs:

Комментарии

0:22:21

0:22:21

0:01:14

0:01:14

0:01:48

0:01:48

0:04:46

0:04:46

0:16:24

0:16:24

0:10:54

0:10:54

0:04:36

0:04:36

0:02:04

0:02:04

0:00:38

0:00:38

0:09:06

0:09:06

0:07:40

0:07:40

0:12:29

0:12:29

0:03:38

0:03:38

0:14:47

0:14:47

0:04:19

0:04:19

0:05:21

0:05:21

0:10:12

0:10:12

0:04:37

0:04:37

0:13:25

0:13:25

0:02:51

0:02:51

0:07:51

0:07:51

0:00:39

0:00:39

0:08:57

0:08:57

0:17:45

0:17:45