filmov

tv

Philosophy of Science 7 - Scientific Revolutions

Показать описание

This video details Thomas Kuhn's philosophy of science, which proposes a cyclical model of scientific development from normal science, to crisis, to revolution, then back to normal science. The important concepts of paradigms and paradigm shifts are explained.

Philosophy of Science 7 - Scientific Revolutions

7. Introduction to Philosophy of Science

Simon Blackburn - Why Philosophy of Science?

LSE Research: Science and Philosophy of Science

Karl Popper, Science, & Pseudoscience: Crash Course Philosophy #8

Colin Blakemore - Why Philosophy of Science?

The Meaning of Knowledge: Crash Course Philosophy #7

Thomas Kuhn: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

philosophy in bangla l philosophy of music and painting

1. Philosophy of Science, Introduction | Course Overview: Philosophy of Natural & Social Science

Philosophy of science Part II

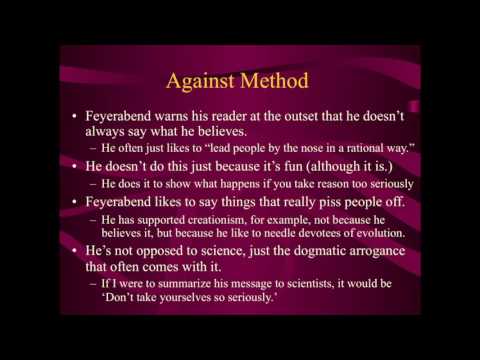

Post-Kuhnian Philosophy of Science: Paul Feyerabend (1 of 2)

Philosophy of Science

Post-Kuhnian Philosophy of Science: Imre Lakatos (1 of 3)

Philosophy of science in fifteen minutes

Philosophy of Science | The Very Short Introductions Podcast | Episode 54

John Wilkins - Philosophy of Science - An Introduction

Immunity and Individuality an Instance of Philosophy in Science: Thomas Pradeu ALS, April 7, 2017

Integrating Science and Contemplative Practice | Philosophy of Meditation #7 with Mark Miller

7 Philosophy Books for Beginners

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein - Why Philosophy of Science

'It seems our existence actually transcends the passage of time' | Sabine Hossenfelder

How to Think Clearly | The Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius

AI & Philosophy — David Chalmers

Комментарии

0:31:20

0:31:20

1:20:19

1:20:19

0:14:27

0:14:27

0:07:39

0:07:39

0:08:57

0:08:57

0:07:45

0:07:45

0:10:12

0:10:12

0:14:31

0:14:31

0:00:51

0:00:51

1:10:35

1:10:35

0:36:46

0:36:46

0:24:15

0:24:15

0:50:54

0:50:54

0:16:59

0:16:59

0:19:07

0:19:07

0:12:46

0:12:46

0:07:15

0:07:15

1:35:27

1:35:27

0:58:02

0:58:02

0:13:38

0:13:38

0:07:04

0:07:04

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:05:34

0:05:34

0:01:00

0:01:00