filmov

tv

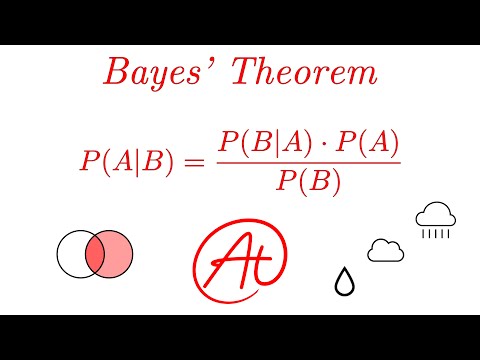

A User's Guide to Bayes' Theorem

Показать описание

What is Bayes' Theorem? How is it used in philosophy, statistics, and beyond? How should it NOT be used? Welcome to the ultimate guide to these questions and more.

OUTLINE

0:00 Intro and outline

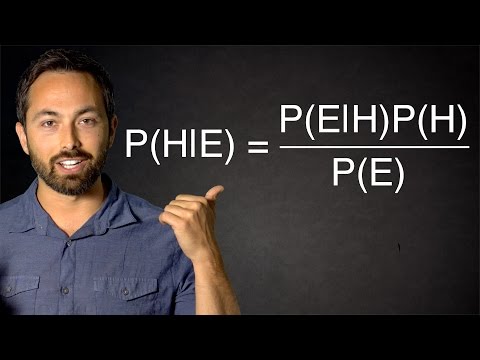

3:10 What is Bayes’ Theorem?

4:50 Belief and credence

14:46 Interpretations of probability

24:52 Epistemic probability

28:32 Bayesian epistemology

30:50 Core normative rules

33:05 Propositional logic background

42:32 Kolmogorov’s axioms

54:25 Dutch Books

57:25 Ratio Formula

1:02:03 Conditionalization principle

1:10:47 Subjective vs. Objective Bayesianism

1:13:50 Bayes’ Theorem: Standard form(s)

1:39:25 Bayes’ Theorem: Odds form

1:53:06 Evidence

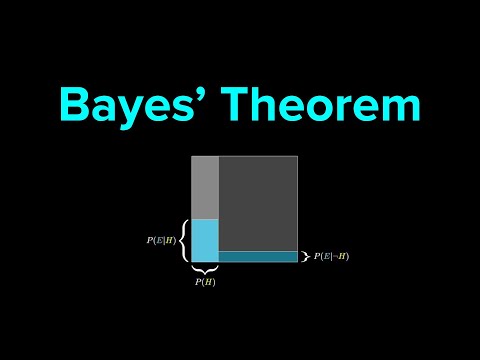

2:09:25 Visualizing Bayes’ Theorem

2:49:41 Common mistakes

2:49:53 Base rate fallacy

2:52:28 Evidence for H vs. Making H probable

2:53:43 Total evidence requirement

2:54:58 Fallacy of understated evidence

2:59:36 Confirmation is comparative

3:01:07 Evidential symmetry

3:07:56 Strength asymmetry

3:11:40 Falsifiability as a virtue

3:12:27 Likelihood ratio rigging

3:19:32 Conclusion and Resources

NOTES

(1) The argument I give around the ten-minute mark admittedly doesn't address the view that (i) credences don't exist, and yet (ii) we can still account for the relevant data about our doxastic lives by appeal to beliefs about probabilities. It also doesn't address the view that while credences exist and are distinct from beliefs, beliefs about probabilities suffice to account for the relevant data.

While I have independent reservations for these views, it's worth noting them nonetheless. The belief/credence part of the video was mainly an exercise in warming listeners up to talk of credences so they would be more receptive to the rest of the video. It's a necessary preamble to the main event: Bayes' Theorem. I grant that a proper defense of belief-credence dualism — and a proper defense of the overly-basic motivations I sketched at the ten-minute mark — would need to contend with these alternative proposals!

CORRECTIONS

(1) At 52:55, I meant to say that the SECOND claim entails the FIRST while the FIRST does not entail the SECOND. Oops!

(2) Thankfully, the audio improves at 28:32! Remind me to never record a solo presentation using Zoom…

(3) Here's an important clarification about the roommate/magical marker example given around 2:07:00. In the video, I was not clear about the content of the hypotheses in question and how this affects their likelihoods and priors. Here is how I should have spelled out the example.

Consider two hypotheses:

H1: My friend wrote on my board

H2: My marker by itself wrote on my board

The data is:

D: "Don't forget to take out the trash!" is written on my board

Now, H1 renders D quite surprising, given that my friend knows all about my diligent habits of taking out the trash, etc. If H1 is true, he would most likely have written something on the board then erased it (since he knows I don't like him touching my board, etc.). And even if he didn't erase it, it would be very odd for him to write this given that he knows I'm super diligent about the trash.

But H2 renders D far, far more surprising. Of all the possible things the marker could conceivably have written on the board by magically floating upwards etc., only an absurdly small fraction are even coherent, let alone English words strung together to compose an intelligible, grammatical, contextually relevant English sentence.

Of course, H1 has higher prior than H2. But the point made in the video stands, since the likelihood of H1 (i.e., P(D|H1)) is very low, but it's still much greater than the likelihood of H2 (i.e., P(D|H2)), and hence data can still be evidence for a hypothesis even though the data is very surprising on that hypothesis.

LINKS

(1) Want the script? Become a patron :)

THE USUAL...

OUTLINE

0:00 Intro and outline

3:10 What is Bayes’ Theorem?

4:50 Belief and credence

14:46 Interpretations of probability

24:52 Epistemic probability

28:32 Bayesian epistemology

30:50 Core normative rules

33:05 Propositional logic background

42:32 Kolmogorov’s axioms

54:25 Dutch Books

57:25 Ratio Formula

1:02:03 Conditionalization principle

1:10:47 Subjective vs. Objective Bayesianism

1:13:50 Bayes’ Theorem: Standard form(s)

1:39:25 Bayes’ Theorem: Odds form

1:53:06 Evidence

2:09:25 Visualizing Bayes’ Theorem

2:49:41 Common mistakes

2:49:53 Base rate fallacy

2:52:28 Evidence for H vs. Making H probable

2:53:43 Total evidence requirement

2:54:58 Fallacy of understated evidence

2:59:36 Confirmation is comparative

3:01:07 Evidential symmetry

3:07:56 Strength asymmetry

3:11:40 Falsifiability as a virtue

3:12:27 Likelihood ratio rigging

3:19:32 Conclusion and Resources

NOTES

(1) The argument I give around the ten-minute mark admittedly doesn't address the view that (i) credences don't exist, and yet (ii) we can still account for the relevant data about our doxastic lives by appeal to beliefs about probabilities. It also doesn't address the view that while credences exist and are distinct from beliefs, beliefs about probabilities suffice to account for the relevant data.

While I have independent reservations for these views, it's worth noting them nonetheless. The belief/credence part of the video was mainly an exercise in warming listeners up to talk of credences so they would be more receptive to the rest of the video. It's a necessary preamble to the main event: Bayes' Theorem. I grant that a proper defense of belief-credence dualism — and a proper defense of the overly-basic motivations I sketched at the ten-minute mark — would need to contend with these alternative proposals!

CORRECTIONS

(1) At 52:55, I meant to say that the SECOND claim entails the FIRST while the FIRST does not entail the SECOND. Oops!

(2) Thankfully, the audio improves at 28:32! Remind me to never record a solo presentation using Zoom…

(3) Here's an important clarification about the roommate/magical marker example given around 2:07:00. In the video, I was not clear about the content of the hypotheses in question and how this affects their likelihoods and priors. Here is how I should have spelled out the example.

Consider two hypotheses:

H1: My friend wrote on my board

H2: My marker by itself wrote on my board

The data is:

D: "Don't forget to take out the trash!" is written on my board

Now, H1 renders D quite surprising, given that my friend knows all about my diligent habits of taking out the trash, etc. If H1 is true, he would most likely have written something on the board then erased it (since he knows I don't like him touching my board, etc.). And even if he didn't erase it, it would be very odd for him to write this given that he knows I'm super diligent about the trash.

But H2 renders D far, far more surprising. Of all the possible things the marker could conceivably have written on the board by magically floating upwards etc., only an absurdly small fraction are even coherent, let alone English words strung together to compose an intelligible, grammatical, contextually relevant English sentence.

Of course, H1 has higher prior than H2. But the point made in the video stands, since the likelihood of H1 (i.e., P(D|H1)) is very low, but it's still much greater than the likelihood of H2 (i.e., P(D|H2)), and hence data can still be evidence for a hypothesis even though the data is very surprising on that hypothesis.

LINKS

(1) Want the script? Become a patron :)

THE USUAL...

Комментарии

3:22:33

3:22:33

0:08:03

0:08:03

0:11:25

0:11:25

0:14:00

0:14:00

0:09:15

0:09:15

0:56:36

0:56:36

0:15:11

0:15:11

0:12:05

0:12:05

0:05:58

0:05:58

0:19:08

0:19:08

0:17:45

0:17:45

0:05:31

0:05:31

0:04:12

0:04:12

0:15:12

0:15:12

0:06:20

0:06:20

0:44:32

0:44:32

0:00:05

0:00:05

0:10:37

0:10:37

0:11:08

0:11:08

0:09:56

0:09:56

0:25:09

0:25:09

0:02:19

0:02:19

0:07:26

0:07:26

0:21:26

0:21:26