filmov

tv

Biofuels: An overview | Climate Now Ep. 1.6

Показать описание

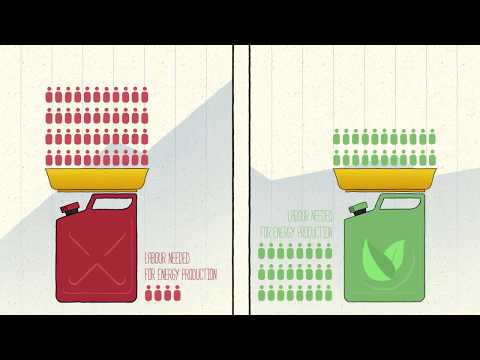

Biomass - such as corn or switchgrass - can be converted into liquid transportation fuels, or #biofuels. Biofuels are attractive because they result in significantly fewer emissions than fossil fuels, but they come with their own set of challenges, including how to minimize the cost of production to compete against fossil fuels.

In this episode, we delve into the process of converting biomass to biofuels and the advancements being made with second, third, and forth-generation biofuels, including waste-to-energy biofuels that are beginning to take shape.

#bioenergy #cleanfuel #cleantransportation

Chapters:

00:00 - How much of our energy comes from biofuels?

00:52 - What is a biofuel and where does it come from?

01:45 - Why Biofuels Result in Fewer CO2 Emissions Than Fossil Fuels

02:30 - How Biofuels Are Made

04:10 - Cost of Biofuels

04:45 - The Four Generations of Biofuel Feedstocks

05:28 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Forest Products

06:42 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Waste and Agricultural Residues

08:20 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Algae

Who is Climate Now?

Climate Now is an educational multimedia platform that produces expert-led, accessible, in-depth podcast and video episodes addressing the climate crisis and its solutions, explaining the science, technologies and key economic and policy considerations at play in the global effort to decarbonize our energy system and larger economy.

Follow us on social media

Transcript:

According to the International Energy Agency, bioenergy provides around 10% of the world’s total primary energy supply. In 2018 alone, 154 billion liters of biofuel were produced worldwide. Additionally, production of biofuels is expected to increase 25% by 2024, as it becomes more competitive in energy markets in Brazil, the US and China. But what is bioenergy? How helpful can it be in the global effort to decarbonize, and how much will it cost to scale up production to help accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels? We spoke with Jerry Tuscan, CEO for the Center for Bioenergy Innovation, and Matt Langholtz, natural resource economist from the Bioenergy Group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. So, what is a biofuel and where does it come from?

Jerry Tuskan:

A biofuel is a liquid fuel derived from biomass, and biomass is just dried plant matter. So imagine taking wood chips or chopped up grass and converting it using bacteria into a liquid transportation fuel. And that becomes a biofuel. By using biofuels, we can displace that petroleum and reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emissions in the transportation sector here in US. So it’s a means of reducing the amount of carbon through capture of growing biomass, Poplar, or switchgrass or other forms of plant biomass, harvesting the above-ground portion and converting that into fuel and leaving the perennial root systems intact in the soil so that that carbon remains fixed in the soil.

This is the difference between CO2 emitted from fossil fuels and CO2 emitted from bioenergy. When burning fossil fuels, carbon is released into the atmosphere after being locked underground for millions of years, thus increasing the total amount of carbon in the biosphere and atmosphere. Biofuels, on the other hand, are part of a closed-loop system in the carbon cycle, and are thus considered to be net-neutral in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon is captured by bioenergy feedstocks, which are turned into fuels, combusted, and the cycle repeats. And if you add carbon capture and storage technology, which captures the carbon at the point of combustion and then stores it underground, biofuels become net-negative.

Before diving into what we know about feedstocks and their economic availability, let’s break down one of the processes used to create biofuels. Here in this diagram, we see that from nonedible plants, there are three components that make up this type of ligno-cellulosic plant matter: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. These structures are what make a plant strong and durable. Once plant matter is grown and collected, it’s taken to a conversion facility where bio-reactors containing bacteria begin to break it down. Plants typically have varying degrees of recalcitrance, meaning how resistant they are to being metabolized by bacteria in the reactor...

In this episode, we delve into the process of converting biomass to biofuels and the advancements being made with second, third, and forth-generation biofuels, including waste-to-energy biofuels that are beginning to take shape.

#bioenergy #cleanfuel #cleantransportation

Chapters:

00:00 - How much of our energy comes from biofuels?

00:52 - What is a biofuel and where does it come from?

01:45 - Why Biofuels Result in Fewer CO2 Emissions Than Fossil Fuels

02:30 - How Biofuels Are Made

04:10 - Cost of Biofuels

04:45 - The Four Generations of Biofuel Feedstocks

05:28 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Forest Products

06:42 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Waste and Agricultural Residues

08:20 - Biofuel Supply Resources: Algae

Who is Climate Now?

Climate Now is an educational multimedia platform that produces expert-led, accessible, in-depth podcast and video episodes addressing the climate crisis and its solutions, explaining the science, technologies and key economic and policy considerations at play in the global effort to decarbonize our energy system and larger economy.

Follow us on social media

Transcript:

According to the International Energy Agency, bioenergy provides around 10% of the world’s total primary energy supply. In 2018 alone, 154 billion liters of biofuel were produced worldwide. Additionally, production of biofuels is expected to increase 25% by 2024, as it becomes more competitive in energy markets in Brazil, the US and China. But what is bioenergy? How helpful can it be in the global effort to decarbonize, and how much will it cost to scale up production to help accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels? We spoke with Jerry Tuscan, CEO for the Center for Bioenergy Innovation, and Matt Langholtz, natural resource economist from the Bioenergy Group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. So, what is a biofuel and where does it come from?

Jerry Tuskan:

A biofuel is a liquid fuel derived from biomass, and biomass is just dried plant matter. So imagine taking wood chips or chopped up grass and converting it using bacteria into a liquid transportation fuel. And that becomes a biofuel. By using biofuels, we can displace that petroleum and reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emissions in the transportation sector here in US. So it’s a means of reducing the amount of carbon through capture of growing biomass, Poplar, or switchgrass or other forms of plant biomass, harvesting the above-ground portion and converting that into fuel and leaving the perennial root systems intact in the soil so that that carbon remains fixed in the soil.

This is the difference between CO2 emitted from fossil fuels and CO2 emitted from bioenergy. When burning fossil fuels, carbon is released into the atmosphere after being locked underground for millions of years, thus increasing the total amount of carbon in the biosphere and atmosphere. Biofuels, on the other hand, are part of a closed-loop system in the carbon cycle, and are thus considered to be net-neutral in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon is captured by bioenergy feedstocks, which are turned into fuels, combusted, and the cycle repeats. And if you add carbon capture and storage technology, which captures the carbon at the point of combustion and then stores it underground, biofuels become net-negative.

Before diving into what we know about feedstocks and their economic availability, let’s break down one of the processes used to create biofuels. Here in this diagram, we see that from nonedible plants, there are three components that make up this type of ligno-cellulosic plant matter: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. These structures are what make a plant strong and durable. Once plant matter is grown and collected, it’s taken to a conversion facility where bio-reactors containing bacteria begin to break it down. Plants typically have varying degrees of recalcitrance, meaning how resistant they are to being metabolized by bacteria in the reactor...

Комментарии

0:09:39

0:09:39

0:05:29

0:05:29

0:07:39

0:07:39

0:02:21

0:02:21

0:01:22

0:01:22

0:22:26

0:22:26

0:43:43

0:43:43

0:02:22

0:02:22

0:21:58

0:21:58

0:11:28

0:11:28

0:08:34

0:08:34

0:00:43

0:00:43

0:20:23

0:20:23

0:00:12

0:00:12

0:21:50

0:21:50

0:00:44

0:00:44

0:56:37

0:56:37

0:15:01

0:15:01

0:03:55

0:03:55

0:00:59

0:00:59

0:02:18

0:02:18

0:04:43

0:04:43

0:06:55

0:06:55

0:03:29

0:03:29