filmov

tv

NASA | Swift Catches Mega Flares from a Mini Star

Показать описание

On April 23, NASA's Swift satellite detected the strongest, hottest, and longest-lasting sequence of stellar flares ever seen from a nearby red dwarf star. The initial blast from this record-setting series of explosions was as much as 10,000 times more powerful than the largest solar flare ever recorded.

At its peak, the flare reached temperatures of 360 million degrees Fahrenheit (200 million Celsius), more than 12 times hotter than the center of the sun.

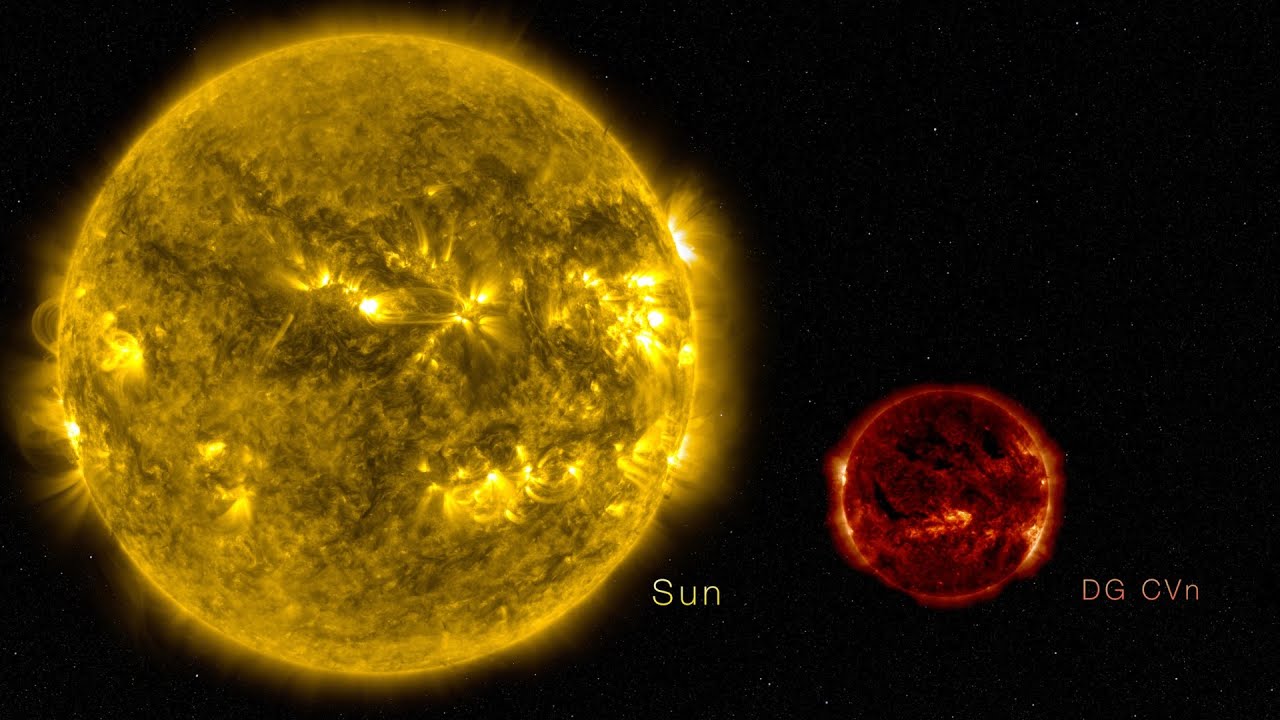

The "superflare" came from one of the stars in a close binary system known as DG Canum Venaticorum, or DG CVn for short, located about 60 light-years away. Both stars are dim red dwarfs with masses and sizes about one-third of our sun's. They orbit each other at about three times Earth's average distance from the sun, which is too close for Swift to determine which star erupted.

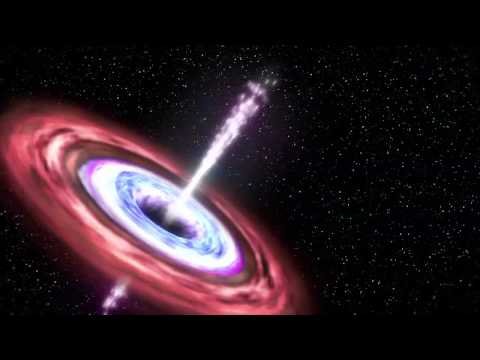

At 5:07 p.m. EDT on April 23, the rising tide of X-rays from DG CVn's superflare triggered Swift's Burst Alert Telescope (BAT). Swift turned to observe the source in greater detail with other instruments and, at the same time, notified astronomers around the globe that a powerful outburst was in progress.

For about three minutes after the BAT trigger, the superflare's X-ray brightness was greater than the combined luminosity of both stars at all wavelengths under normal conditions.

The largest solar explosions are classified as extraordinary, or X class, solar flares based on their X-ray emission. The biggest flare ever seen from the sun occurred in November 2003 and is rated as X 45. But if the flare on DG CVn were viewed from a planet the same distance as Earth is from the sun and measured the same way, it would have been ranked 10,000 times greater, at about X 100,000.

How can a star just a third the size of the sun produce such a giant eruption? The key factor is its rapid spin, a crucial ingredient for amplifying magnetic fields. The flaring star in DG CVn rotates in under a day, about 30 or more times faster than our sun. The sun also rotated much faster in its youth and may well have produced superflares of its own, but, fortunately for us, it no longer appears capable of doing so.

Like our videos? Subscribe to NASA's Goddard Shorts HD podcast:

Or find NASA Goddard Space Flight Center on Facebook:

Or find us on Twitter:

At its peak, the flare reached temperatures of 360 million degrees Fahrenheit (200 million Celsius), more than 12 times hotter than the center of the sun.

The "superflare" came from one of the stars in a close binary system known as DG Canum Venaticorum, or DG CVn for short, located about 60 light-years away. Both stars are dim red dwarfs with masses and sizes about one-third of our sun's. They orbit each other at about three times Earth's average distance from the sun, which is too close for Swift to determine which star erupted.

At 5:07 p.m. EDT on April 23, the rising tide of X-rays from DG CVn's superflare triggered Swift's Burst Alert Telescope (BAT). Swift turned to observe the source in greater detail with other instruments and, at the same time, notified astronomers around the globe that a powerful outburst was in progress.

For about three minutes after the BAT trigger, the superflare's X-ray brightness was greater than the combined luminosity of both stars at all wavelengths under normal conditions.

The largest solar explosions are classified as extraordinary, or X class, solar flares based on their X-ray emission. The biggest flare ever seen from the sun occurred in November 2003 and is rated as X 45. But if the flare on DG CVn were viewed from a planet the same distance as Earth is from the sun and measured the same way, it would have been ranked 10,000 times greater, at about X 100,000.

How can a star just a third the size of the sun produce such a giant eruption? The key factor is its rapid spin, a crucial ingredient for amplifying magnetic fields. The flaring star in DG CVn rotates in under a day, about 30 or more times faster than our sun. The sun also rotated much faster in its youth and may well have produced superflares of its own, but, fortunately for us, it no longer appears capable of doing so.

Like our videos? Subscribe to NASA's Goddard Shorts HD podcast:

Or find NASA Goddard Space Flight Center on Facebook:

Or find us on Twitter:

Комментарии

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:01:16

0:01:16

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:03:51

0:03:51

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:01:04

0:01:04

0:04:02

0:04:02

0:02:40

0:02:40

0:08:54

0:08:54

0:01:05

0:01:05

0:05:27

0:05:27

0:00:26

0:00:26

0:00:41

0:00:41

0:02:30

0:02:30

0:01:01

0:01:01

0:01:09

0:01:09

0:05:27

0:05:27

0:01:04

0:01:04

0:00:22

0:00:22