filmov

tv

Simulation Reveals Spiraling Supermassive Black Holes

Показать описание

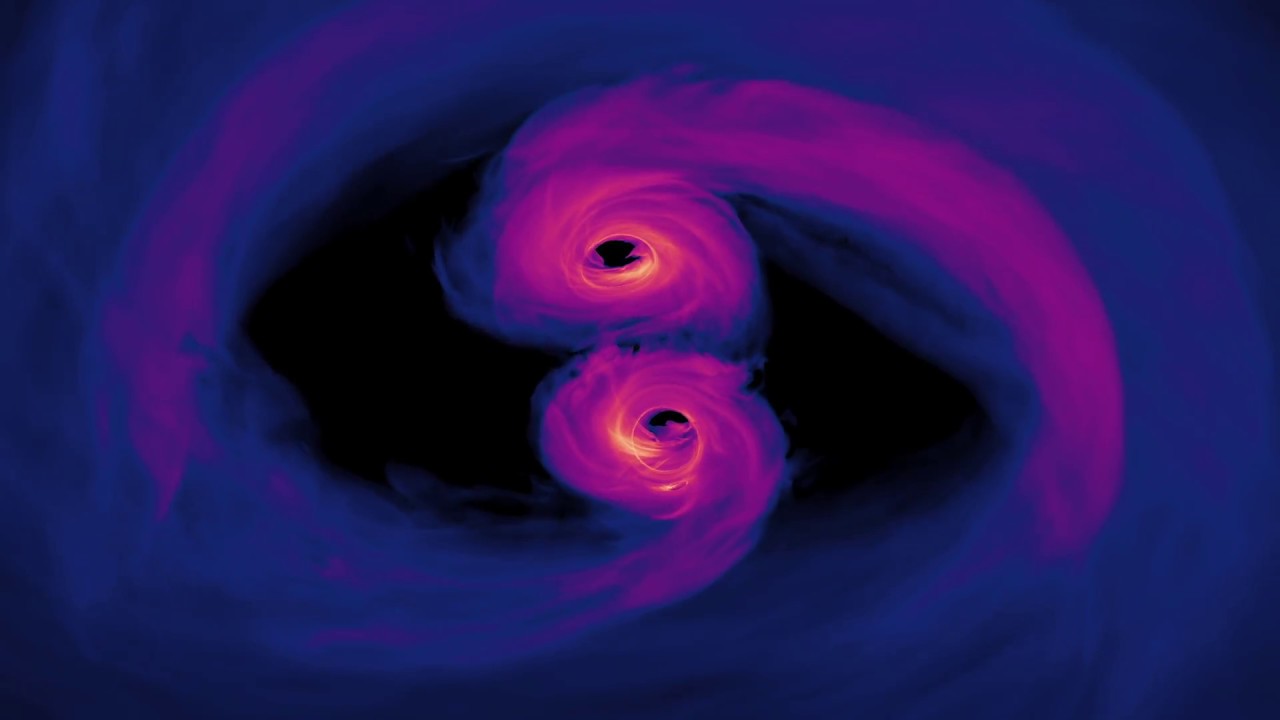

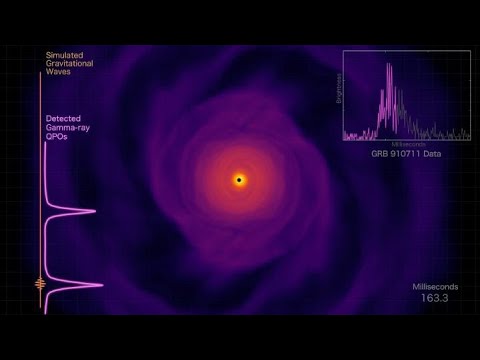

A new model is bringing scientists a step closer to understanding the kinds of light signals produced when two supermassive black holes, which are millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun, spiral toward a collision. For the first time, a new computer simulation that fully incorporates the physical effects of Einstein's general theory of relativity shows that gas in such systems will glow predominantly in ultraviolet and X-ray light.

Just about every galaxy the size of our own Milky Way or larger contains a monster black hole at its center. Observations show galaxy mergers occur frequently in the universe, but so far no one has seen a merger of these giant black holes.

Scientists have detected merging stellar-mass black holes -- which range from around three to several dozen solar masses -- using the National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Gravitational waves are space-time ripples traveling at the speed of light. They are created when massive orbiting objects like black holes and neutron stars spiral together and merge.

Supermassive mergers will be much more difficult to find than their stellar-mass cousins. One reason ground-based observatories can't detect gravitational waves from these events is because Earth itself is too noisy, shaking from seismic vibrations and gravitational changes from atmospheric disturbances. The detectors must be in space, like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) led by ESA (the European Space Agency) and planned for launch in the 2030s.

But supermassive binaries nearing collision may have one thing stellar-mass binaries lack -- a gas-rich environment. Scientists suspect the supernova explosion that creates a stellar black hole also blows away most of the surrounding gas. The black hole consumes what little remains so quickly there isn't much left to glow when the merger happens.

Supermassive binaries, on the other hand, result from galaxy mergers. Each supersized black hole brings along an entourage of gas and dust clouds, stars and planets. Scientists think a galaxy collision propels much of this material toward the central black holes, which consume it on a time scale similar to that needed for the binary to merge. As the black holes near, magnetic and gravitational forces heat the remaining gas, producing light astronomers should be able to see.

The new simulation shows three orbits of a pair of supermassive black holes only 40 orbits from merging. The models reveal the light emitted at this stage of the process may be dominated by UV light with some high-energy X-rays, similar to what's seen in any galaxy with a well-fed supermassive black hole.

Three regions of light-emitting gas glow as the black holes merge, all connected by streams of hot gas: a large ring encircling the entire system, called the circumbinary disk, and two smaller ones around each black hole, called mini disks. All these objects emit predominantly UV light. When gas flows into a mini disk at a high rate, the disk's UV light interacts with each black hole's corona, a region of high-energy subatomic particles above and below the disk. This interaction produces X-rays. When the accretion rate is lower, UV light dims relative to the X-rays.

Based on the simulation, the researchers expect X-rays emitted by a near-merger will be brighter and more variable than X-rays seen from single supermassive black holes. The pace of the changes links to both the orbital speed of gas located at the inner edge of the circumbinary disk as well as that of the merging black holes.

The simulation ran on the National Center for Supercomputing Applications' Blue Waters supercomputer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Modeling three orbits of the system took 46 days on 9,600 computing cores.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Music: "Games Show Sphere 01" from Killer Tracks

Follow NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Just about every galaxy the size of our own Milky Way or larger contains a monster black hole at its center. Observations show galaxy mergers occur frequently in the universe, but so far no one has seen a merger of these giant black holes.

Scientists have detected merging stellar-mass black holes -- which range from around three to several dozen solar masses -- using the National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Gravitational waves are space-time ripples traveling at the speed of light. They are created when massive orbiting objects like black holes and neutron stars spiral together and merge.

Supermassive mergers will be much more difficult to find than their stellar-mass cousins. One reason ground-based observatories can't detect gravitational waves from these events is because Earth itself is too noisy, shaking from seismic vibrations and gravitational changes from atmospheric disturbances. The detectors must be in space, like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) led by ESA (the European Space Agency) and planned for launch in the 2030s.

But supermassive binaries nearing collision may have one thing stellar-mass binaries lack -- a gas-rich environment. Scientists suspect the supernova explosion that creates a stellar black hole also blows away most of the surrounding gas. The black hole consumes what little remains so quickly there isn't much left to glow when the merger happens.

Supermassive binaries, on the other hand, result from galaxy mergers. Each supersized black hole brings along an entourage of gas and dust clouds, stars and planets. Scientists think a galaxy collision propels much of this material toward the central black holes, which consume it on a time scale similar to that needed for the binary to merge. As the black holes near, magnetic and gravitational forces heat the remaining gas, producing light astronomers should be able to see.

The new simulation shows three orbits of a pair of supermassive black holes only 40 orbits from merging. The models reveal the light emitted at this stage of the process may be dominated by UV light with some high-energy X-rays, similar to what's seen in any galaxy with a well-fed supermassive black hole.

Three regions of light-emitting gas glow as the black holes merge, all connected by streams of hot gas: a large ring encircling the entire system, called the circumbinary disk, and two smaller ones around each black hole, called mini disks. All these objects emit predominantly UV light. When gas flows into a mini disk at a high rate, the disk's UV light interacts with each black hole's corona, a region of high-energy subatomic particles above and below the disk. This interaction produces X-rays. When the accretion rate is lower, UV light dims relative to the X-rays.

Based on the simulation, the researchers expect X-rays emitted by a near-merger will be brighter and more variable than X-rays seen from single supermassive black holes. The pace of the changes links to both the orbital speed of gas located at the inner edge of the circumbinary disk as well as that of the merging black holes.

The simulation ran on the National Center for Supercomputing Applications' Blue Waters supercomputer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Modeling three orbits of the system took 46 days on 9,600 computing cores.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Music: "Games Show Sphere 01" from Killer Tracks

Follow NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Комментарии

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:01:19

0:01:19

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:00:07

0:00:07

0:01:58

0:01:58

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:01:40

0:01:40

0:00:54

0:00:54

0:02:14

0:02:14

0:01:58

0:01:58

0:00:11

0:00:11

0:03:11

0:03:11

0:00:16

0:00:16

0:00:51

0:00:51

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:00:33

0:00:33

0:00:35

0:00:35

0:01:01

0:01:01

0:00:26

0:00:26

0:00:20

0:00:20

0:00:30

0:00:30