filmov

tv

Alexander Luria: The Working Brain & the controversy over localization versus function (9-5-2023).

Показать описание

Alexander Romanovich Luria (16 July 1902 – 14 August 1977) was a Soviet neuropsychologist and is often credited as the father of modern neuropsychology. He designed extensive and original batteries of neuropsychological tests during his clinical work with brain-injured victims of World War II (Wikipedia).

Luria was born to Jewish parents in Kazan, east of Moscow. His father, Roman Albertovich Luria was a professor at the University of Kazan and became a founder of the Kazan Institute of Advanced Medical Education. His mother, Evgenia Viktorovna Khaskina was a practicing dentist (Wikipedia).

Alexander studied at Kazan State University and graduated in 1921. He met Lev Vygotsky in 1924 and was greatly influenced by him. The two psychologists started the Vygotsky Circle that became the Vygotsky-Luria Circle. He was appointed Doctor of Medical Sciences in 1943, Professor in 1944 and established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Society. He also exchanged letters with Sigmund Freud (Wikipedia).

During WWII, he treated hundreds of hospitalized patients with traumatic brain injury but kept up with his research. He wrote Traumatic Aphasia (1947), but was published only in Russia and not published in English until 1972. His explanations “formulated an original conception of the neural organization of speech and its disorders (aphasias) that differed significantly from the existing western conceptions about aphasia” (Homskaya, 2001).

Luria’s magnum opus, Higher Cortical Functions in Man (1962), is still a much-used psychological textbook which has been translated into many languages. He also wrote The Working Brain (1973) as a supplement to Higher Cortical Functions in Man. The two books are "among Luria's major works in neuropsychology, most fully reflecting all the aspects (theoretical, clinical, experimental) of this new discipline" (Homskaya, 2001).

The purpose of Higher Cortical Functions in Man is to “analyze the disturbances of higher mental functions caused by local lesions of the brain” and start to understand the mental processes based on the deficits and symptoms of the disturbances (Luria, 1962). The Working Brain took the next step towards understanding “the internal structure of mental activity” with the emerging details “of the basic principles of neuropsychological research” (Luria, 1973).

Among the many themes of Luria’s decades of research about neuropsychology, resolving the controversy of localization (or narrow localization) versus function became, in his words, a ‘crisis” (Luria, 1973).

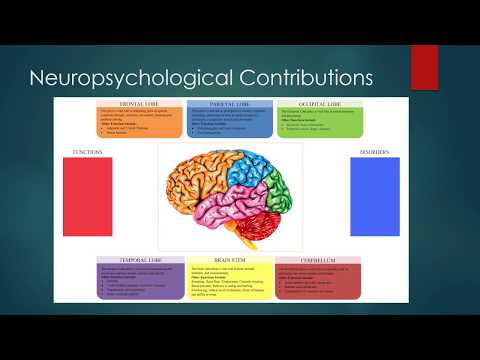

Paul Broca had discovered that a lesion in a particular place on the left side of the brain was considered the ‘language center’ and was focused on and localized in, what became, the Broca’s area. But other imagined ‘centers’ with ‘functional maps’ had arrived with centers for concepts, writing, mathematical calculation, reading, and orientation in space spurring the debate between localization and function (Luria, 1973).

As Broca established the Broca’s area and aphasia, Hughlings Jackson established a new hypothesis that “approached from the standpoint of the level of their construction rather than that of their localization in particular areas of the brain” (Luria, 1973). As Jackson said, “Whilst I believe that the hinder part of the left frontal convolution is the part most often damaged, I do not localise speech in any such small part of the brain. To locate the damage which destroys speech and to localise speech are two different things” (Brain, 1915, pp. 81, Head, 2014/1926, pp. 50).

Luria’s challenge was that the “fundamental forms of conscious activity must be considered as complex functional systems; consequently, the basic approach to their ‘localization’ in the cerebral cortex must be radically altered” (Luria, 1973, pp 30).

Luria explained that mental functions are incredibly complex and widespread, and are not limited to one circumscribed location or another as the only place where those functions operate within the brain. As Luria stated, those systems “cannot be localized in narrow zones of the cortex or in isolated cell groups, but must be organized in systems of concertedly working zones, each of which performs its role in complex functional system, and which may be located in completely different and often far distant areas of the brain” (Luria, 1973, pp 31).

As noted by Luria, it has been difficult to reimagine the operation of the different parts of the brain, not as confined centers, locations, or functions but as the “essential apparatus for organizing intellectual activity as a whole” (Luria, 1973, pp 340). But in Pavlov’s words, recorded by Luria, “…it is abundantly obvious here that, for longer than we can tell, the truth is immeasurably greater than all the tiny fragments we have so far been able to discover…” (Luria, 1947, Lecture 22). This is the case, especially when the whole of the brain really is greater than the sum of its parts.

Luria was born to Jewish parents in Kazan, east of Moscow. His father, Roman Albertovich Luria was a professor at the University of Kazan and became a founder of the Kazan Institute of Advanced Medical Education. His mother, Evgenia Viktorovna Khaskina was a practicing dentist (Wikipedia).

Alexander studied at Kazan State University and graduated in 1921. He met Lev Vygotsky in 1924 and was greatly influenced by him. The two psychologists started the Vygotsky Circle that became the Vygotsky-Luria Circle. He was appointed Doctor of Medical Sciences in 1943, Professor in 1944 and established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Society. He also exchanged letters with Sigmund Freud (Wikipedia).

During WWII, he treated hundreds of hospitalized patients with traumatic brain injury but kept up with his research. He wrote Traumatic Aphasia (1947), but was published only in Russia and not published in English until 1972. His explanations “formulated an original conception of the neural organization of speech and its disorders (aphasias) that differed significantly from the existing western conceptions about aphasia” (Homskaya, 2001).

Luria’s magnum opus, Higher Cortical Functions in Man (1962), is still a much-used psychological textbook which has been translated into many languages. He also wrote The Working Brain (1973) as a supplement to Higher Cortical Functions in Man. The two books are "among Luria's major works in neuropsychology, most fully reflecting all the aspects (theoretical, clinical, experimental) of this new discipline" (Homskaya, 2001).

The purpose of Higher Cortical Functions in Man is to “analyze the disturbances of higher mental functions caused by local lesions of the brain” and start to understand the mental processes based on the deficits and symptoms of the disturbances (Luria, 1962). The Working Brain took the next step towards understanding “the internal structure of mental activity” with the emerging details “of the basic principles of neuropsychological research” (Luria, 1973).

Among the many themes of Luria’s decades of research about neuropsychology, resolving the controversy of localization (or narrow localization) versus function became, in his words, a ‘crisis” (Luria, 1973).

Paul Broca had discovered that a lesion in a particular place on the left side of the brain was considered the ‘language center’ and was focused on and localized in, what became, the Broca’s area. But other imagined ‘centers’ with ‘functional maps’ had arrived with centers for concepts, writing, mathematical calculation, reading, and orientation in space spurring the debate between localization and function (Luria, 1973).

As Broca established the Broca’s area and aphasia, Hughlings Jackson established a new hypothesis that “approached from the standpoint of the level of their construction rather than that of their localization in particular areas of the brain” (Luria, 1973). As Jackson said, “Whilst I believe that the hinder part of the left frontal convolution is the part most often damaged, I do not localise speech in any such small part of the brain. To locate the damage which destroys speech and to localise speech are two different things” (Brain, 1915, pp. 81, Head, 2014/1926, pp. 50).

Luria’s challenge was that the “fundamental forms of conscious activity must be considered as complex functional systems; consequently, the basic approach to their ‘localization’ in the cerebral cortex must be radically altered” (Luria, 1973, pp 30).

Luria explained that mental functions are incredibly complex and widespread, and are not limited to one circumscribed location or another as the only place where those functions operate within the brain. As Luria stated, those systems “cannot be localized in narrow zones of the cortex or in isolated cell groups, but must be organized in systems of concertedly working zones, each of which performs its role in complex functional system, and which may be located in completely different and often far distant areas of the brain” (Luria, 1973, pp 31).

As noted by Luria, it has been difficult to reimagine the operation of the different parts of the brain, not as confined centers, locations, or functions but as the “essential apparatus for organizing intellectual activity as a whole” (Luria, 1973, pp 340). But in Pavlov’s words, recorded by Luria, “…it is abundantly obvious here that, for longer than we can tell, the truth is immeasurably greater than all the tiny fragments we have so far been able to discover…” (Luria, 1947, Lecture 22). This is the case, especially when the whole of the brain really is greater than the sum of its parts.

Комментарии

0:16:29

0:16:29

0:13:52

0:13:52

0:04:28

0:04:28

0:02:26

0:02:26

0:13:17

0:13:17

0:04:19

0:04:19

0:03:04

0:03:04

0:03:30

0:03:30

0:05:07

0:05:07

0:03:59

0:03:59

0:52:01

0:52:01

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:00:15

0:00:15

0:01:45

0:01:45

0:05:26

0:05:26

0:00:10

0:00:10

0:11:13

0:11:13

0:06:01

0:06:01

0:03:11

0:03:11

0:20:09

0:20:09

3:10:57

3:10:57

0:00:51

0:00:51

0:01:52

0:01:52

0:02:31

0:02:31