filmov

tv

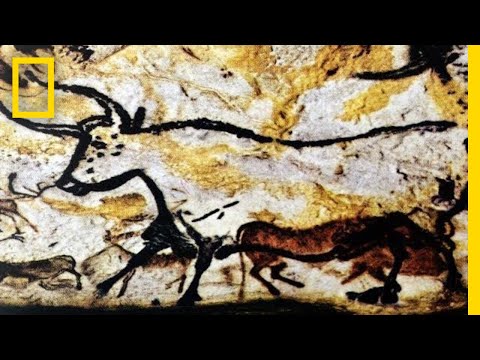

What can Stone Age art tell us about extinct animals?

Показать описание

From Lascaux to Chauvet to Australia, in this video I discuss the many illustrations of now extinct prehistoric animals and how they can be significant to paleontologists. Additionally, artwork created by our long dead ancestors can actually tell us a lot about prehistory we wouldn't know otherwise from cultural norms to religious beliefs. So I've taken the time to examine what prehistoric art can tell us. We will talk about everything from Irish Elk to Marsupial Lions so I hope you enjoy!

Most Images are taken from Wikimedia Commons

Most Images are taken from Wikimedia Commons

What can Stone Age art tell us about extinct animals?

Cave Art 101 | National Geographic

Stone Age Art: Lascaux Cave Paintings

Cave Art | Stone Age Paintings (How they did it?)

Prehistoric Art for Kids - Cave Art - Art History Lesson 001

Stone Age | Prehistoric age | Paleolithic | Mesolithic | Neolithic | Stone Age Humans

Living in the Stone Age: Making Stone Age Art

How to draw prehistoric art- Cave art inspired artwork for KIDS!

Evolution of weapons #art #history #stones #stoneage #technology #technologia #upsc #ssc #old #funny

The Three Stone Age Eras

Brian Cox visits Europe's oldest known cave paintings - Human Universe: Episode 5 Preview - BBC

How to make a Stone Age inspired cave painting #prehistoricart #caveart

Prehistoric Art Tutorial Inspired by Lascaux Cave - Art With Trista

Stone Age to Bronze Age I Pottery

The Stone Age | Prehistoric age | Stone Age Humans | Video for kids

Stone Age Art

Cave Art: Complex Paintings from the Stone Age

Stone Age art gets a global audience with Lascaux roadshow

The Stone Age Man | Life Millions Of Years Ago | The Dr Binocs Show | Peekaboo Kidz

Stone Age Tools | Evolution of Stone Tools | Stone Tool Industries | Tools in the Paleolithic Age

This Stone-Age Weapon fought against the Rapier?! #sword #history #weapon

How to make a Stone Age cave painting, with Sophie Kirtley

ARTH2710 Lecture02 Prehistoric Art

tools and weapons of early man

Комментарии

0:17:47

0:17:47

0:03:19

0:03:19

0:01:21

0:01:21

0:05:42

0:05:42

0:06:41

0:06:41

0:07:55

0:07:55

0:03:17

0:03:17

0:08:38

0:08:38

0:00:16

0:00:16

0:03:26

0:03:26

0:03:19

0:03:19

0:18:59

0:18:59

0:04:45

0:04:45

0:02:32

0:02:32

0:02:51

0:02:51

0:00:54

0:00:54

0:03:28

0:03:28

0:01:53

0:01:53

0:06:46

0:06:46

0:07:38

0:07:38

0:00:42

0:00:42

0:03:46

0:03:46

1:40:43

1:40:43

0:00:05

0:00:05