filmov

tv

Randomised Control Trials

Показать описание

Randomised control trials (RCT) are often referred to as the ‘gold standard’ in quantitative experimental research design. An RCT is a particular way of evaluating the effects of an intervention, project or aid programme that allows researchers to determine whether changes recorded at the end of an intervention were due to aspects of that intervention or if they occurred by chance.

In times of financial constraint and increasing demands for accountability and transparency in international development work RCTs can be seen as a useful tool in helping to understand what works or doesn’t work and how well something works.

Randomised control trials have become increasingly popular in international development policy provision as they are thought to be one of the most effective ways of ensuring rigorous and transparent research that is not possible to achieve through other forms of evaluation.

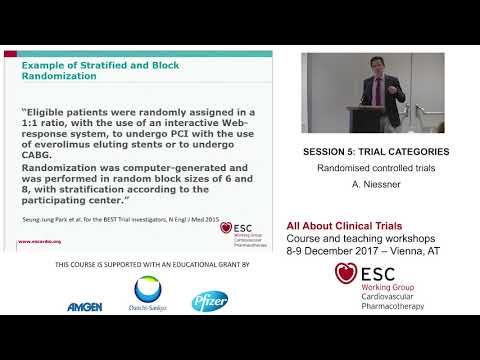

The RCT design originated in medical and biological research where it is commonly used as a means of determining the effects of drug or treatment interventions for particular medical conditions. Usually an RCT in this context will include a ‘double-blind’ condition where both researchers and participants are unaware of who has been assigned to the drug group and who is to be given a placebo. This is to help prevent any expectations of the drugs influencing the outcomes of the study or biasing results.

In an international development context, it is not always possible to eliminate this type of bias as interventions will usually require some change in practice that will be noticeable to participants and researchers. However, RCTs are still considered one of the best ways of ensuring that research findings are as free from bias as possible and determining whether an intervention has an effect or not and therefore helping to ensure that limited funds are spent on programmes that actually work and are not wasted.

Designing a Randomised Control Trial (RCT)

Randomised control trials have a number of unique features to their design that sets them apart from other research approaches.

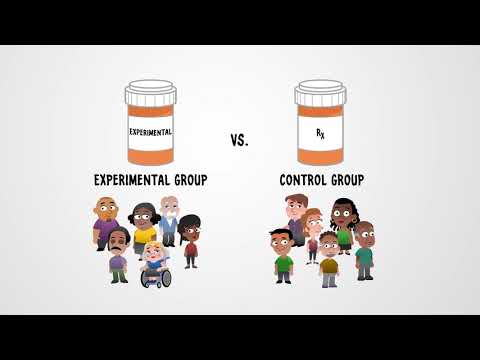

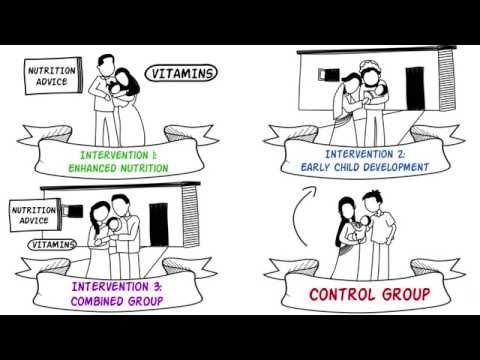

Most importantly, groups (often existing village groups or camps in international development trials) are randomly assigned to receive an intervention, or a level of an intervention (the experimental group), or to receive no intervention (the control group). The control group is used to provide a baseline measure of outcomes when there has been no intervention. Each group should therefore be identical statistically in every way with the only difference being the level of intervention that they receive.

For example, if you want to find out the best way to ensure as many children as possible receive necessary immunisations to prevent life threatening diseases, you could design a RCT to test different types of incentives. The control group would receive services as normal and would serve as a comparison to the intervention group.

The types of interventions that you use to incentivise people to take up immunisation programmes will depend on your knowledge and experience in this area. You may believe, based on past research, that the main barrier to immunising children is a lack of access to medical centres and that making access easier is the answer. For this group you could set up mobile immunisation centres that visit camps or villages periodically thus ensuring everyone has easy access. At the end of a set amount of time (e.g. six months or a year) you would measure the rates of immunisation throughout the control group compared to the intervention group.

If at the end of your trial you find that there is a significant increase in the proportion of children being immunised in the experimental group compared to the control group, you can confidently conclude that making access to healthcare services in this way is an effective way of increasing immunisations. However, you may find that there is little or no difference between the groups at the end of your intervention. In this case you can conclude that lack of access to services is not a major barrier to the take up of immunisations and that spending money on increasing access is not justified.

In times of financial constraint and increasing demands for accountability and transparency in international development work RCTs can be seen as a useful tool in helping to understand what works or doesn’t work and how well something works.

Randomised control trials have become increasingly popular in international development policy provision as they are thought to be one of the most effective ways of ensuring rigorous and transparent research that is not possible to achieve through other forms of evaluation.

The RCT design originated in medical and biological research where it is commonly used as a means of determining the effects of drug or treatment interventions for particular medical conditions. Usually an RCT in this context will include a ‘double-blind’ condition where both researchers and participants are unaware of who has been assigned to the drug group and who is to be given a placebo. This is to help prevent any expectations of the drugs influencing the outcomes of the study or biasing results.

In an international development context, it is not always possible to eliminate this type of bias as interventions will usually require some change in practice that will be noticeable to participants and researchers. However, RCTs are still considered one of the best ways of ensuring that research findings are as free from bias as possible and determining whether an intervention has an effect or not and therefore helping to ensure that limited funds are spent on programmes that actually work and are not wasted.

Designing a Randomised Control Trial (RCT)

Randomised control trials have a number of unique features to their design that sets them apart from other research approaches.

Most importantly, groups (often existing village groups or camps in international development trials) are randomly assigned to receive an intervention, or a level of an intervention (the experimental group), or to receive no intervention (the control group). The control group is used to provide a baseline measure of outcomes when there has been no intervention. Each group should therefore be identical statistically in every way with the only difference being the level of intervention that they receive.

For example, if you want to find out the best way to ensure as many children as possible receive necessary immunisations to prevent life threatening diseases, you could design a RCT to test different types of incentives. The control group would receive services as normal and would serve as a comparison to the intervention group.

The types of interventions that you use to incentivise people to take up immunisation programmes will depend on your knowledge and experience in this area. You may believe, based on past research, that the main barrier to immunising children is a lack of access to medical centres and that making access easier is the answer. For this group you could set up mobile immunisation centres that visit camps or villages periodically thus ensuring everyone has easy access. At the end of a set amount of time (e.g. six months or a year) you would measure the rates of immunisation throughout the control group compared to the intervention group.

If at the end of your trial you find that there is a significant increase in the proportion of children being immunised in the experimental group compared to the control group, you can confidently conclude that making access to healthcare services in this way is an effective way of increasing immunisations. However, you may find that there is little or no difference between the groups at the end of your intervention. In this case you can conclude that lack of access to services is not a major barrier to the take up of immunisations and that spending money on increasing access is not justified.

0:01:55

0:01:55

0:03:29

0:03:29

0:03:57

0:03:57

0:01:30

0:01:30

0:04:50

0:04:50

0:01:38

0:01:38

0:20:34

0:20:34

0:52:15

0:52:15

0:10:01

0:10:01

0:05:00

0:05:00

0:19:12

0:19:12

0:03:52

0:03:52

0:08:56

0:08:56

0:34:29

0:34:29

0:08:47

0:08:47

0:06:39

0:06:39

0:05:02

0:05:02

0:02:26

0:02:26

0:07:34

0:07:34

1:56:00

1:56:00

0:03:57

0:03:57

0:08:40

0:08:40

0:00:58

0:00:58

0:08:48

0:08:48