filmov

tv

The Fentanyl Surge - Part 1

Показать описание

As Heroin and OxyContin Fade, Powerful and Cheap Fentanyl Kills 30,000 Per Year

Just when the U.S. began winning the war on prescription opioid misuse, synthetic fentanyl smuggled from China and Mexico has created an “unprecedented” increase in overdose deaths.

by Chris Adams, National Press Foundation

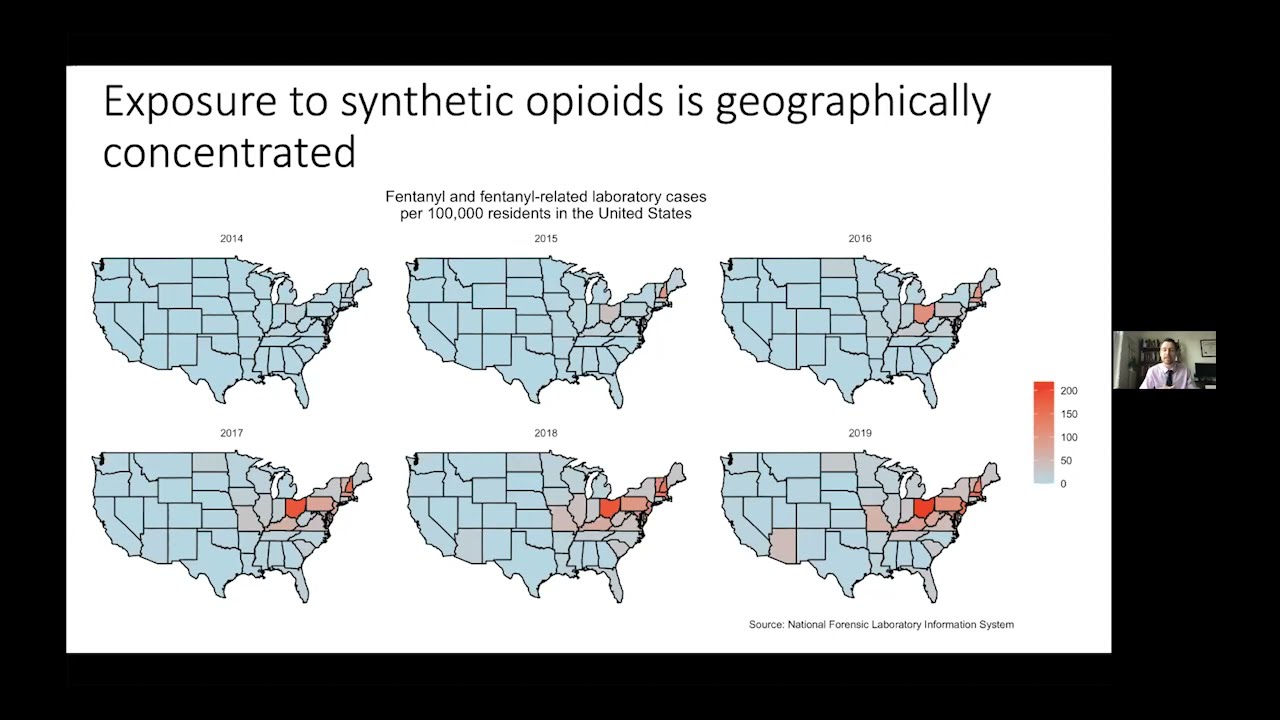

In many states, Oxy is old news – fentanyl is king. While deaths from prescription opioids such as OxyContin have begun to recede, overdoses from synthetic opioids – variants of fentanyl – have skyrocketed. Prescription opioids deaths never topped 20,000 a year; fentanyl deaths now exceed 30,000. Those official numbers are from 2019, the latest available; that lag in data is another problem for public health officials. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s most recent, preliminary numbers indicate that about 90,000 people died from drug overdoses in the 12 months ended in September 2020. “What has happened in the last few years has been this unprecedented rise in the number of deaths involving synthetic opioids,” said Bryce Pardo, a policy researcher with the Rand Corp. who authored a major study on the issue. He and other researchers call it the “third wave” of the epidemic: prescription opioid deaths started climbing in the late 1990s, heroin deaths surged in 2010 and fentanyl deaths began to rise starting in about 2015.

China and Mexico are the top fentanyl suppliers. In the 1970s, more than 100 people died from fentanyl in California. In the 1980s, a fentanyl product sold as “China White heroin” showed up in Pennsylvania. In the 1990s and 2000s, other fentanyl variants emerged in big cities. These episodes were short-lived – three years or less. The current fentanyl outbreak is going on seven years. Almost all fentanyl is now smuggled in from China and Mexico. It is so potent and arrives in such tiny quantities that it is almost impossible to interdict. In the past, when law enforcement tried to interdict heroin at a port of entry or an international mail facility, “it was like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” Pardo said. “Well, now with fentanyl, it’s almost like trying to find a bacteria colony on that needle in that haystack.”

Fentanyl is lucrative. Manufacturing fentanyl is not as easy as making methamphetamine, but it is much easier than cultivating a poppy crop to produce heroin – and far more profitable. Producing heroin takes months and yields a product that has three times the power of morphine (the measurement unit used to compare the strength of opioids). A batch of synthetic fentanyl can be completed in a “matter of a few days,” Pardo said, the product is 50 to 100 times as powerful as morphine. Heroin fetches more money in the illicit marketplace, but the difference in potency makes fentanyl far more lucrative. “For suppliers, fentanyl is the future,” Pardo said.

Speaker: Bryce Pardo, Policy Researcher, Rand Corp.

This program is sponsored by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, with support from Arnold Ventures. NPF retains sole responsibility for programming and content.

Just when the U.S. began winning the war on prescription opioid misuse, synthetic fentanyl smuggled from China and Mexico has created an “unprecedented” increase in overdose deaths.

by Chris Adams, National Press Foundation

In many states, Oxy is old news – fentanyl is king. While deaths from prescription opioids such as OxyContin have begun to recede, overdoses from synthetic opioids – variants of fentanyl – have skyrocketed. Prescription opioids deaths never topped 20,000 a year; fentanyl deaths now exceed 30,000. Those official numbers are from 2019, the latest available; that lag in data is another problem for public health officials. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s most recent, preliminary numbers indicate that about 90,000 people died from drug overdoses in the 12 months ended in September 2020. “What has happened in the last few years has been this unprecedented rise in the number of deaths involving synthetic opioids,” said Bryce Pardo, a policy researcher with the Rand Corp. who authored a major study on the issue. He and other researchers call it the “third wave” of the epidemic: prescription opioid deaths started climbing in the late 1990s, heroin deaths surged in 2010 and fentanyl deaths began to rise starting in about 2015.

China and Mexico are the top fentanyl suppliers. In the 1970s, more than 100 people died from fentanyl in California. In the 1980s, a fentanyl product sold as “China White heroin” showed up in Pennsylvania. In the 1990s and 2000s, other fentanyl variants emerged in big cities. These episodes were short-lived – three years or less. The current fentanyl outbreak is going on seven years. Almost all fentanyl is now smuggled in from China and Mexico. It is so potent and arrives in such tiny quantities that it is almost impossible to interdict. In the past, when law enforcement tried to interdict heroin at a port of entry or an international mail facility, “it was like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” Pardo said. “Well, now with fentanyl, it’s almost like trying to find a bacteria colony on that needle in that haystack.”

Fentanyl is lucrative. Manufacturing fentanyl is not as easy as making methamphetamine, but it is much easier than cultivating a poppy crop to produce heroin – and far more profitable. Producing heroin takes months and yields a product that has three times the power of morphine (the measurement unit used to compare the strength of opioids). A batch of synthetic fentanyl can be completed in a “matter of a few days,” Pardo said, the product is 50 to 100 times as powerful as morphine. Heroin fetches more money in the illicit marketplace, but the difference in potency makes fentanyl far more lucrative. “For suppliers, fentanyl is the future,” Pardo said.

Speaker: Bryce Pardo, Policy Researcher, Rand Corp.

This program is sponsored by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, with support from Arnold Ventures. NPF retains sole responsibility for programming and content.

Комментарии

1:02:42

1:02:42

0:18:04

0:18:04

0:04:13

0:04:13

0:01:02

0:01:02

0:14:39

0:14:39

0:21:16

0:21:16

0:02:21

0:02:21

0:25:56

0:25:56

0:04:30

0:04:30

0:20:07

0:20:07

0:01:01

0:01:01

0:02:01

0:02:01

0:00:17

0:00:17

0:05:06

0:05:06

0:00:21

0:00:21

0:00:36

0:00:36

0:14:28

0:14:28

0:03:38

0:03:38

0:02:40

0:02:40

0:04:04

0:04:04

0:02:09

0:02:09

0:02:29

0:02:29

0:00:16

0:00:16

0:18:52

0:18:52