filmov

tv

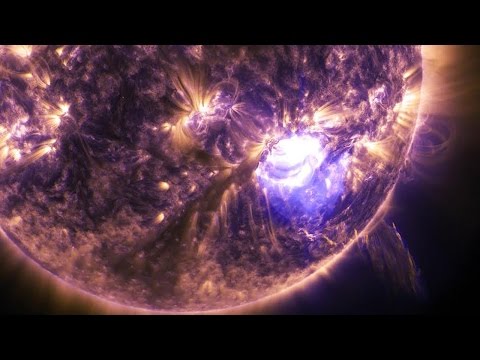

NASA SDO - Van Gogh Sun

Показать описание

A crucial, and often underappreciated, facet of science lies in deciding how to turn the raw numbers of data into useful, understandable information -- often through graphs and images. Such visualization techniques are needed for everything from making a map of planetary orbits based on nightly measurements of where they are in the sky to colorizing normally invisible light such as X-rays to produce "images" of the Sun.

More information, of course, requires more complex visualizations and occasionally such images are not just informative, but beautiful too.

Such is the case with a new technique created by Nicholeen Viall, a solar scientist at NASA Goddard in Greenbelt, Md. She creates images of the Sun reminiscent of Van Gogh, with broad strokes of bright color splashed across a yellow background. But it's science, not art. The color of each pixel contains a wealth of information about the 12-hour history of cooling and heating at that particular spot on the Sun. That heat history holds clues to the mechanisms that drive the temperature and movements of the sun's atmosphere, or corona.

To look at the corona from a fresh perspective, Viall created a new kind of picture, making use of the high resolution provided by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). SDO's Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) provides images of the Sun in 10 different wavelengths, each approximately corresponding to a single temperature of material. Therefore, when one looks at the wavelength of 171 Angstroms, for example, one sees all the material in the sun's atmosphere that is a million degrees Kelvin. By looking at an area of the Sun in different wavelengths, one can get a sense of how different swaths of material change temperature. If an area seems bright in a wavelength that shows a hotter temperature an hour before it becomes bright in a wavelength that shows a cooler temperature, one can gather information about how that region has changed over time.

Viall's images show a wealth of reds, oranges, and yellow, meaning that over a 12-hour period the material appear to be cooling. Obviously there must have been heating in the process as well, since the corona isn't on a one-way temperature slide down to zero degrees. Any kind of steady heating throughout the corona would have shown up in Viall's images, so she concludes that the heating must be quick and impulsive -- so fast that it doesn't show up in her images. This lends credence to those theories that say numerous nanobursts of energy help heat the corona.

Credit: NASA SDO

More information, of course, requires more complex visualizations and occasionally such images are not just informative, but beautiful too.

Such is the case with a new technique created by Nicholeen Viall, a solar scientist at NASA Goddard in Greenbelt, Md. She creates images of the Sun reminiscent of Van Gogh, with broad strokes of bright color splashed across a yellow background. But it's science, not art. The color of each pixel contains a wealth of information about the 12-hour history of cooling and heating at that particular spot on the Sun. That heat history holds clues to the mechanisms that drive the temperature and movements of the sun's atmosphere, or corona.

To look at the corona from a fresh perspective, Viall created a new kind of picture, making use of the high resolution provided by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). SDO's Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) provides images of the Sun in 10 different wavelengths, each approximately corresponding to a single temperature of material. Therefore, when one looks at the wavelength of 171 Angstroms, for example, one sees all the material in the sun's atmosphere that is a million degrees Kelvin. By looking at an area of the Sun in different wavelengths, one can get a sense of how different swaths of material change temperature. If an area seems bright in a wavelength that shows a hotter temperature an hour before it becomes bright in a wavelength that shows a cooler temperature, one can gather information about how that region has changed over time.

Viall's images show a wealth of reds, oranges, and yellow, meaning that over a 12-hour period the material appear to be cooling. Obviously there must have been heating in the process as well, since the corona isn't on a one-way temperature slide down to zero degrees. Any kind of steady heating throughout the corona would have shown up in Viall's images, so she concludes that the heating must be quick and impulsive -- so fast that it doesn't show up in her images. This lends credence to those theories that say numerous nanobursts of energy help heat the corona.

Credit: NASA SDO

Комментарии

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:02:07

0:08:09

0:08:09

0:01:26

0:01:26

0:06:32

0:06:32

0:02:38

0:02:38

0:00:22

0:00:22

0:02:33

0:02:33

0:01:41

0:01:41

0:01:41

0:01:41

0:00:30

0:00:30

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:01:08

0:01:08

0:03:58

0:03:58

0:00:41

0:00:41

0:01:54

0:01:54

0:03:30

0:03:30

0:01:54

0:01:54

0:00:40

0:00:40

0:00:08

0:00:08

0:00:50

0:00:50