filmov

tv

Chinese Doesn't Have Many Syllables (And Why That's Interesting)

Показать описание

Comment on the change of title in the pinned comment.

An exploration of the unusually restrictive syllable structures of Standard Chinese.

Where I put "颜" for "to grind", this should have been "研".

Written and Created by Me.

Artwork and Additional Editing by kvd102

except the table and the night/day thing, I did those, don't you take that away from me, don't let someone else have the credit here!

0:00 Modern Standard Chinese

1:10 Standard Chinese Phonemes

1:55 English Phonotactics

2:50 Standard Chinese Phonotactics

4:05 Standard Chinese Syllables

4:39 Morphemes

5:05 How does Chinese Handle This?

Translations:

vlrfsg - Japanese

deacu daniel - Romanian

Anqi Chen (!00qi) - Standard Mandarin

Leeuwe van den Heuvel - Dutch

James Morris-Wyatt - Spanish

kijetesantakalu palisa - Esperanto (lol)

уля - Ukrainian

Izet - Bosnian

LPG - Taiwanese Mandarin (Traditional Chinese)

emyds - Portuguese (Brazil)

PD6 - Portuguese (Europe)

An exploration of the unusually restrictive syllable structures of Standard Chinese.

Where I put "颜" for "to grind", this should have been "研".

Written and Created by Me.

Artwork and Additional Editing by kvd102

except the table and the night/day thing, I did those, don't you take that away from me, don't let someone else have the credit here!

0:00 Modern Standard Chinese

1:10 Standard Chinese Phonemes

1:55 English Phonotactics

2:50 Standard Chinese Phonotactics

4:05 Standard Chinese Syllables

4:39 Morphemes

5:05 How does Chinese Handle This?

Translations:

vlrfsg - Japanese

deacu daniel - Romanian

Anqi Chen (!00qi) - Standard Mandarin

Leeuwe van den Heuvel - Dutch

James Morris-Wyatt - Spanish

kijetesantakalu palisa - Esperanto (lol)

уля - Ukrainian

Izet - Bosnian

LPG - Taiwanese Mandarin (Traditional Chinese)

emyds - Portuguese (Brazil)

PD6 - Portuguese (Europe)

Chinese Doesn't Have Many Syllables (And Why That's Interesting)

Chinese Doesn’t Have Syllables (And Why It’s a Problem)

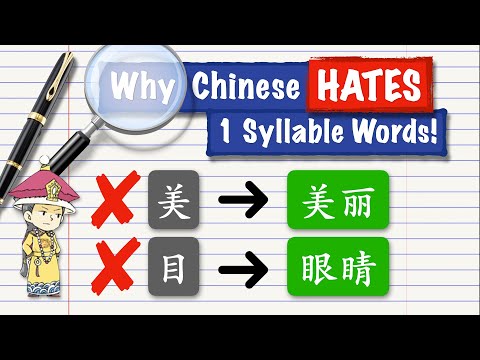

Why Chinese HATES 1 Syllable Words

Why is Chinese OBSESSED w/ 2 Syllable Words?

Chinese Isn't (Really) A Language...

WE HAVE THE MOST WORDS 📖 #countryhumans #xane

Counting the Phonemes in a Language

Chinese - Syllables - S&E Academy

Initials and finals of Chinese syllables/beginners level/lesson 7/pinyin mandarin

japanese hiragana syllable song

Word-Level Stress in Mandarin (Part 1): 4 Types of Words and How to Stress Them!

Master Chinese Tones in 1 Minute // #learningmandarin

Top 3 Easiest Languages to Learn

Master the Chinese 'Q' Sound: All Syllables with Common Words!

Top 3 Hardest Languages to Learn

Here’s how you can separate the pinyin chart into 4 different categories #pinyin #studychinese

Free business Chinese course - Beginner Chinese -PINYIN Pronunciation Lesson: Syllables Part 2

Initials and finals of Pinyin syllables 2 (difficult)/beginner's level/pinyin mandarin

COMPLETE CHINESE PINYIN CHART - So Few Syllables - The Advantage & Disadvantage?!

How to say 'have to' & 'don't have to' in Chinese - Chinese Learning Ti...

Chinese Word Logic Explained in 10 Minutes

Initials and finals of Chinese Pinyin syllables review/beginner's level/HSK 1

Can you hear the difference? Japanese Pronunciation 🇯🇵

Top 10 Hardest Languages to Learn

Комментарии

0:07:49

0:07:49

0:11:39

0:11:39

0:06:02

0:06:02

0:10:07

0:10:07

0:06:35

0:06:35

0:00:18

0:00:18

0:09:11

0:09:11

0:03:29

0:03:29

0:08:25

0:08:25

0:00:21

0:00:21

0:18:03

0:18:03

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:00:43

0:00:43

0:12:14

0:12:14

0:00:43

0:00:43

0:00:58

0:00:58

0:01:41

0:01:41

0:13:05

0:13:05

0:02:44

0:02:44

0:01:11

0:01:11

0:09:56

0:09:56

0:07:27

0:07:27

0:00:30

0:00:30

0:00:31

0:00:31