filmov

tv

How Do Propellers Work? The History of the Marine Propeller.

Показать описание

The history of the propeller, explained and animated for the Mariner's Mirror Podcast.The modern day Marine Propeller has a long history. First designs for screw propulsion go back thousands of years. The original displacement screw on which propellers are based, was first invented by Archimedes in the third century B.C. The ARCHIMEDES SCREW was first putto use for displacing grain and other cereal crops. A simple and effective way of moving large amounts to load farm vehicles and warehouses.

This original concept is still in wide use today in farming and other industries. You can find an Archimedes screw on modern combine harvesters for example. It was soon realized that the same principle could be used to displace liquids, providing an effective way of causing a flow of material.When the Archimedes Screw is submerged, a thrust is created by the displacement of water. This is because of Newton’s third law... for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction.The difference in pressures at each end of the screw produces a thrust, forcing it to move through the water.

The next logical step was to fit the assembly to the underside of a vessel to drive it. Sure enough, the displacement was enough to propel the vessel. At this time steam powered ships were using rotary side paddles for propulsion and this method was still considered the most efficient. Nevertheless, the concept was progressed and developed to try and improve speed and mobility. In Eighteen thirty-five a major

breakthrough came about when, during a test trial, the screw was accidentally damaged. Part of it was dislodged, leaving the remaining part to propel the ship. It was discovered that this actually improved the performance due to a shorter screw having less drag.

A new shorter screw propeller was developed and was first fitted to THE ARCHIMEDES. This paved the way for the modern propellers of today. The first one to successfully utilize the screw propeller familiar to us today was BRUNEL who developed a 6-bladed version in Eighteen forty-seven. This was fitted to The GREAT BRITAIN, the first screw-propelled and iron vessel to cross the Atlantic. Since the Brunel model, the fundamental design of marine propellers has changed very little, reinforcing the ingenuity of this clever device. So what lies behind this design that has stood the test of time?

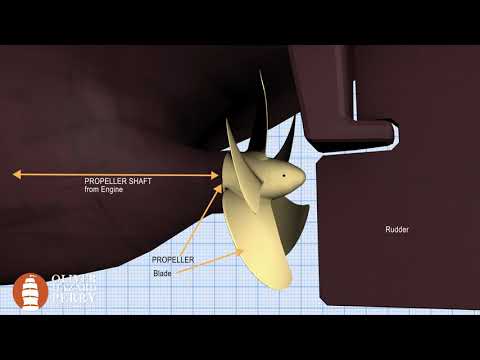

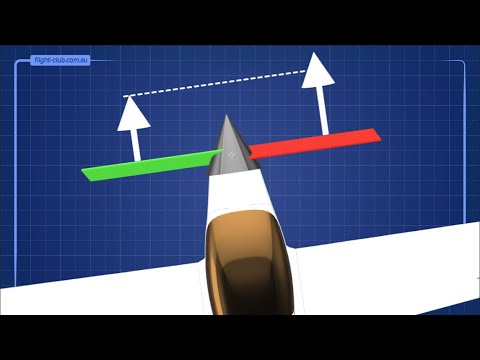

Marine propellers achieve propulsion by using their angled blades to generate thrust. It’s much the same principle that an aeroplane adopts to generate lift. If an aerofoil has no angle, the pressures are equal above and below it. In this case, a boat will have no thrust and an aircraft will have no lift. When an angle of attack is introduced, the flow hits the underside causing a high pressure area as the wing is pushed upwards by it. A low pressure area forms above the wing as the flow is sucked into the area of displacement. To illustrate how a marine propeller works, a propeller blade can be compared to an aircraft wing. A basic two-bladed propeller is essentially two wings... If you turn one around so that it’s facing the other way, the pressure differential will also inverse causing an opposing thrust.

Throw in a central pivot between them and the opposing forces will cause the propeller to turn. Similarly, if a propeller is powered to rotate, it will cause the same pressure differences, producing thrust to the rear... Remember Newton’s law? The propeller will want to react and move forward.

So there you have it. The trusty propeller has so far withstood opposition from other methods of marine propulsion. There have been many variations and advances in designs which make certain propellers more suitable for their various applications. But essentially, the brilliant concept of screw propulsion remains unchallenged.

This original concept is still in wide use today in farming and other industries. You can find an Archimedes screw on modern combine harvesters for example. It was soon realized that the same principle could be used to displace liquids, providing an effective way of causing a flow of material.When the Archimedes Screw is submerged, a thrust is created by the displacement of water. This is because of Newton’s third law... for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction.The difference in pressures at each end of the screw produces a thrust, forcing it to move through the water.

The next logical step was to fit the assembly to the underside of a vessel to drive it. Sure enough, the displacement was enough to propel the vessel. At this time steam powered ships were using rotary side paddles for propulsion and this method was still considered the most efficient. Nevertheless, the concept was progressed and developed to try and improve speed and mobility. In Eighteen thirty-five a major

breakthrough came about when, during a test trial, the screw was accidentally damaged. Part of it was dislodged, leaving the remaining part to propel the ship. It was discovered that this actually improved the performance due to a shorter screw having less drag.

A new shorter screw propeller was developed and was first fitted to THE ARCHIMEDES. This paved the way for the modern propellers of today. The first one to successfully utilize the screw propeller familiar to us today was BRUNEL who developed a 6-bladed version in Eighteen forty-seven. This was fitted to The GREAT BRITAIN, the first screw-propelled and iron vessel to cross the Atlantic. Since the Brunel model, the fundamental design of marine propellers has changed very little, reinforcing the ingenuity of this clever device. So what lies behind this design that has stood the test of time?

Marine propellers achieve propulsion by using their angled blades to generate thrust. It’s much the same principle that an aeroplane adopts to generate lift. If an aerofoil has no angle, the pressures are equal above and below it. In this case, a boat will have no thrust and an aircraft will have no lift. When an angle of attack is introduced, the flow hits the underside causing a high pressure area as the wing is pushed upwards by it. A low pressure area forms above the wing as the flow is sucked into the area of displacement. To illustrate how a marine propeller works, a propeller blade can be compared to an aircraft wing. A basic two-bladed propeller is essentially two wings... If you turn one around so that it’s facing the other way, the pressure differential will also inverse causing an opposing thrust.

Throw in a central pivot between them and the opposing forces will cause the propeller to turn. Similarly, if a propeller is powered to rotate, it will cause the same pressure differences, producing thrust to the rear... Remember Newton’s law? The propeller will want to react and move forward.

So there you have it. The trusty propeller has so far withstood opposition from other methods of marine propulsion. There have been many variations and advances in designs which make certain propellers more suitable for their various applications. But essentially, the brilliant concept of screw propulsion remains unchallenged.

Комментарии

0:05:05

0:05:05

0:17:51

0:17:51

0:05:48

0:05:48

0:01:58

0:01:58

0:06:25

0:06:25

0:03:41

0:03:41

0:04:11

0:04:11

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:12:54

0:12:54

0:06:37

0:06:37

0:10:13

0:10:13

0:08:40

0:08:40

0:00:11

0:00:11

0:00:49

0:00:49

0:02:12

0:02:12

0:08:16

0:08:16

0:03:30

0:03:30

0:01:04

0:01:04

0:08:02

0:08:02

0:08:53

0:08:53

0:03:13

0:03:13

0:00:39

0:00:39

0:28:49

0:28:49

0:10:13

0:10:13