filmov

tv

Tort Law - Duty of Care

Показать описание

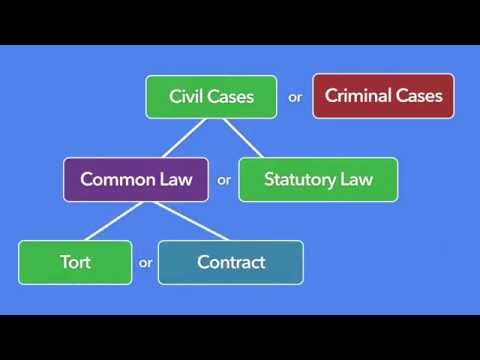

The duty of care is one of the key aspects of tort law and provides a foundation for claimants when bringing a case.

The origin of the duty of care comes from Brett MR in Heaven v Pender [1883] but the most famous formulation is the neighbour principle from Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] by Lord Atkin.

Circumstances in which a duty of care can exist were broadened a great deal in the case of Anns v Merton LBC [1978] by Lord Wilberforce who included policy factors but cases such as Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1983] showed that this was too far wide-ranging and opened up liability for even pure economic loss.

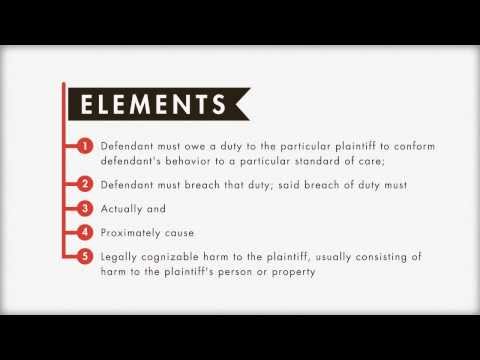

The law was narrowed in Hill v CC of W Yorkshire [1988] and the modern test now comes from Caparo Industries plc v Dickman [1990] where three factors are considered: 1) Foreseeability 2) Proximity and 3) whether it is fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty of care.

The duty of care is based on the objective standard or 'the man on the Clapham omnibus'. The law is relatively forgiving of the ordinary man (Wells v Cooper [1958]; The Ogopogo [1972]).

A variation in the standard has been applied to children (McHale v Watson [1966]; Latham v Johnson [1913]) but has been applied strictly to drivers (Nettleship v Weston [1971]; Broome v Perkins [1987]).

Professionals are held to the standard of a normal person in their profession and the question of what is to be considered normal practice can be derived from the Bolam test (Bolam v Friern Hospital [1957]) where it was held that if the practice is supported by a substantial body of opinion within the profession then it will be allowed within the duty of care.

The Hand formula is useful when making a judgment and can be expressed as the incursion of liability where the burden is less than the possibility of damage occurring multiplied by the loss incurred. See further: Latimer v AEC Ltd. [1953]; Bolton v Stone [1951]; Paris v Stepney BC [1951]; Haley v London Electricity Board [1965].

The burden of proof is assessed on the balance of probabilities and in certain circumstances res ipsa loquitur can be said to apply as per Erle CJ in Scott v London and St. Katherine Docks Co. [1865].

The origin of the duty of care comes from Brett MR in Heaven v Pender [1883] but the most famous formulation is the neighbour principle from Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] by Lord Atkin.

Circumstances in which a duty of care can exist were broadened a great deal in the case of Anns v Merton LBC [1978] by Lord Wilberforce who included policy factors but cases such as Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1983] showed that this was too far wide-ranging and opened up liability for even pure economic loss.

The law was narrowed in Hill v CC of W Yorkshire [1988] and the modern test now comes from Caparo Industries plc v Dickman [1990] where three factors are considered: 1) Foreseeability 2) Proximity and 3) whether it is fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty of care.

The duty of care is based on the objective standard or 'the man on the Clapham omnibus'. The law is relatively forgiving of the ordinary man (Wells v Cooper [1958]; The Ogopogo [1972]).

A variation in the standard has been applied to children (McHale v Watson [1966]; Latham v Johnson [1913]) but has been applied strictly to drivers (Nettleship v Weston [1971]; Broome v Perkins [1987]).

Professionals are held to the standard of a normal person in their profession and the question of what is to be considered normal practice can be derived from the Bolam test (Bolam v Friern Hospital [1957]) where it was held that if the practice is supported by a substantial body of opinion within the profession then it will be allowed within the duty of care.

The Hand formula is useful when making a judgment and can be expressed as the incursion of liability where the burden is less than the possibility of damage occurring multiplied by the loss incurred. See further: Latimer v AEC Ltd. [1953]; Bolton v Stone [1951]; Paris v Stepney BC [1951]; Haley v London Electricity Board [1965].

The burden of proof is assessed on the balance of probabilities and in certain circumstances res ipsa loquitur can be said to apply as per Erle CJ in Scott v London and St. Katherine Docks Co. [1865].

Комментарии

0:03:25

0:03:25

0:17:31

0:17:31

0:08:28

0:08:28

0:02:58

0:02:58

0:13:40

0:13:40

0:10:20

0:10:20

0:10:41

0:10:41

0:10:50

0:10:50

0:06:51

0:06:51

0:00:58

0:00:58

0:11:55

0:11:55

0:00:56

0:00:56

0:09:15

0:09:15

0:14:09

0:14:09

0:09:45

0:09:45

0:12:18

0:12:18

0:07:03

0:07:03

0:06:34

0:06:34

0:11:52

0:11:52

0:06:16

0:06:16

1:08:46

1:08:46

0:08:32

0:08:32

0:03:40

0:03:40

0:21:33

0:21:33