filmov

tv

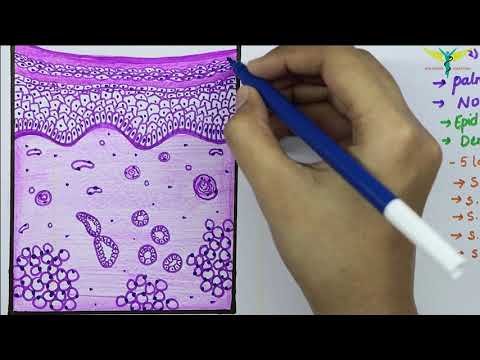

Histology of Thick Skin/Glabrous skin

Показать описание

Skin is the largest organ of the body.

Hairs are only found in thin skin, and not in the thick skin present on the fingertips, palms and soles of your feet.

Three layers of skin:

The epidermis: a thin outer portion, that is the keratinised stratified squamous epithelium of skin. The epidermis is important for the protective function of skin. The basal layers of this epithelium are folded to form dermal papillae. Thin skin contains four types of cellular layers, and thick skin contains five. Click here to find out more about the epidermis and its layers.

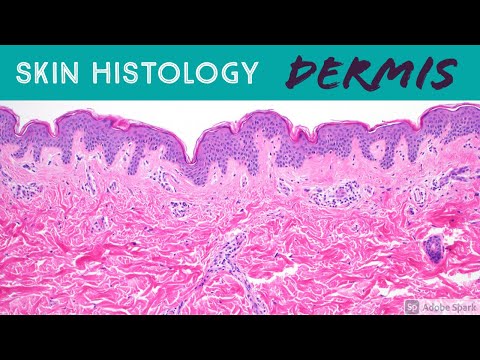

The dermis: a thicker inner portion. This is the connective tissue layer of skin. It is important for sensation, protection and thermoregulation. It contains nerves, the blood supply, fibroblasts, etc, as well as sweat glands, which open out onto the surface of the skin, and in some regions, hair. The apical layers of the dermis are folded, to form dermal papillae, which are particularly prominent in thick skin.

The hypodermis. This layer is underneath the dermis, and merges with it. It mainly contains adipose tissue and sweat glands. The adipose tissue has metabolic functions: it is resonsible for production of vitamin D, and triglycerides.

Thick Skin: The Epidermis

Although often thought of as a simple sheet of tissue, the skin is truly an organ, one of the largest and most complex of the organs in the human body. The skin is a covering and as such performs many functions. Of all the skin covering the body, none is tougher or thicker than that covering the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The toughness and thickness of palmar and plantar skin makes its inclusion in a single thin section for electron-microscopic investigation difficult.

Fortunately, the skin of the fingertip is much thinner and more delicate and yet retains all the histologic landmarks of thick skin.

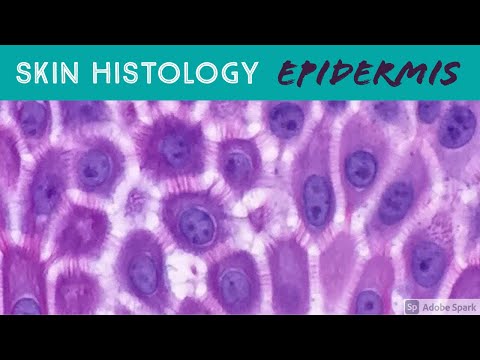

Figures A and B at right are a matched pair of light and electron micrographs of serial cross sections taken through the skin of the fingertip of the squirrel monkey. Like all skin, it is made up of two major regions-the Epidermis, a keratinized stratified Squamous Epithelium, and the Dermis, a thick underlying layer of connective tissue. Here, the Epidermis is so extensive and thick that it nearly fills the field. Only a small part of the Dermis in the form of the edge of a dermal papilla (DP) is visible. (Dermal papillae are ridges that project into the Epidermis, push it up, and are responsible for the complex patterns of whorls and lines in fingerprints). Skin has many functions, one of which is protecting the underlying soft, wet tissues from abrasion and dehydration. The protective function of the skin resides in the physical properties of the flattened, horny cells, or Squames, that cover its surface. The superficial layer of the Epidermis, the Stratum Corneum(SC), consists of dead cells very much like flat scales that are filled with the fibrous protein Keratin.

These cells are periodically shed from the surface of the skin. In some cases, they are rapidly worn away by physical contact with tennis rackets, lawn mowers, or, in the case of the squirrel monkey, branches. The tough, expendable surface cells would be of little use unless they were regularly replaced, and it comes as no surprise that they are, due to the special properties of the remainder of the Epidermis upon which the stratum corneum sits.

Replacement of worn-out surface Squames is ultimately a function of mitotic activity in the deepest layer of the Epidermis, the stratum germinativurn (SG). The stratum germinativurn lies atop the Dermis and consists of a single layer of large, polygonal cells. As mitotic activity occurs, daughter cells migrate upward into the next layer, the Stratum Spinosum (SS). The cells of the Stratum Spinosum have a spiny appearance because of the large number of small desmosomes that bind them together. As cells move upward through the stratum spinosum, they synthesize Keratin. When their Cytoplasm contains a noticeable number of dark, electron-dense Keratohyalin Granules, the cells form a layer known as the granular layer, or Stratum Granulosum (SGr). As the cells move upward through the Stratum Granulosum, their cytoplasmic organelles degenerate and the cells become packed with Keratin, until, in the clear layer, or Stratum Lucidum (SL), they have no nuclei and are completely devoid of organelles. The keratinized cells then migrate (or rather are pushed) up into the horny layer, or Stratum Corneum, where they serve to protect the body until lost to the outside world.

Hairs are only found in thin skin, and not in the thick skin present on the fingertips, palms and soles of your feet.

Three layers of skin:

The epidermis: a thin outer portion, that is the keratinised stratified squamous epithelium of skin. The epidermis is important for the protective function of skin. The basal layers of this epithelium are folded to form dermal papillae. Thin skin contains four types of cellular layers, and thick skin contains five. Click here to find out more about the epidermis and its layers.

The dermis: a thicker inner portion. This is the connective tissue layer of skin. It is important for sensation, protection and thermoregulation. It contains nerves, the blood supply, fibroblasts, etc, as well as sweat glands, which open out onto the surface of the skin, and in some regions, hair. The apical layers of the dermis are folded, to form dermal papillae, which are particularly prominent in thick skin.

The hypodermis. This layer is underneath the dermis, and merges with it. It mainly contains adipose tissue and sweat glands. The adipose tissue has metabolic functions: it is resonsible for production of vitamin D, and triglycerides.

Thick Skin: The Epidermis

Although often thought of as a simple sheet of tissue, the skin is truly an organ, one of the largest and most complex of the organs in the human body. The skin is a covering and as such performs many functions. Of all the skin covering the body, none is tougher or thicker than that covering the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The toughness and thickness of palmar and plantar skin makes its inclusion in a single thin section for electron-microscopic investigation difficult.

Fortunately, the skin of the fingertip is much thinner and more delicate and yet retains all the histologic landmarks of thick skin.

Figures A and B at right are a matched pair of light and electron micrographs of serial cross sections taken through the skin of the fingertip of the squirrel monkey. Like all skin, it is made up of two major regions-the Epidermis, a keratinized stratified Squamous Epithelium, and the Dermis, a thick underlying layer of connective tissue. Here, the Epidermis is so extensive and thick that it nearly fills the field. Only a small part of the Dermis in the form of the edge of a dermal papilla (DP) is visible. (Dermal papillae are ridges that project into the Epidermis, push it up, and are responsible for the complex patterns of whorls and lines in fingerprints). Skin has many functions, one of which is protecting the underlying soft, wet tissues from abrasion and dehydration. The protective function of the skin resides in the physical properties of the flattened, horny cells, or Squames, that cover its surface. The superficial layer of the Epidermis, the Stratum Corneum(SC), consists of dead cells very much like flat scales that are filled with the fibrous protein Keratin.

These cells are periodically shed from the surface of the skin. In some cases, they are rapidly worn away by physical contact with tennis rackets, lawn mowers, or, in the case of the squirrel monkey, branches. The tough, expendable surface cells would be of little use unless they were regularly replaced, and it comes as no surprise that they are, due to the special properties of the remainder of the Epidermis upon which the stratum corneum sits.

Replacement of worn-out surface Squames is ultimately a function of mitotic activity in the deepest layer of the Epidermis, the stratum germinativurn (SG). The stratum germinativurn lies atop the Dermis and consists of a single layer of large, polygonal cells. As mitotic activity occurs, daughter cells migrate upward into the next layer, the Stratum Spinosum (SS). The cells of the Stratum Spinosum have a spiny appearance because of the large number of small desmosomes that bind them together. As cells move upward through the stratum spinosum, they synthesize Keratin. When their Cytoplasm contains a noticeable number of dark, electron-dense Keratohyalin Granules, the cells form a layer known as the granular layer, or Stratum Granulosum (SGr). As the cells move upward through the Stratum Granulosum, their cytoplasmic organelles degenerate and the cells become packed with Keratin, until, in the clear layer, or Stratum Lucidum (SL), they have no nuclei and are completely devoid of organelles. The keratinized cells then migrate (or rather are pushed) up into the horny layer, or Stratum Corneum, where they serve to protect the body until lost to the outside world.

Комментарии

0:05:25

0:05:25

0:05:37

0:05:37

0:02:42

0:02:42

0:06:51

0:06:51

0:27:50

0:27:50

0:04:53

0:04:53

0:06:30

0:06:30

0:16:23

0:16:23

0:09:46

0:09:46

0:00:15

0:00:15

0:19:59

0:19:59

0:17:44

0:17:44

0:00:35

0:00:35

0:13:28

0:13:28

0:11:47

0:11:47

0:12:38

0:12:38

0:03:22

0:03:22

0:02:41

0:02:41

0:07:17

0:07:17

0:46:55

0:46:55

0:09:00

0:09:00

0:14:39

0:14:39

0:16:23

0:16:23

0:04:00

0:04:00