filmov

tv

How Does a Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Rocket Work?

Показать описание

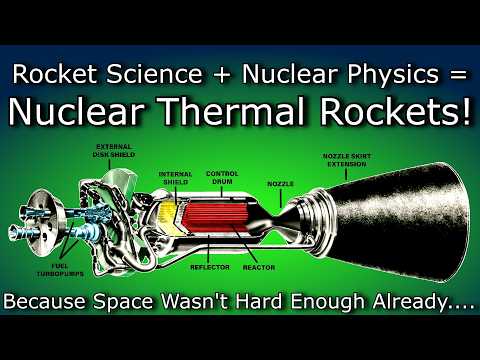

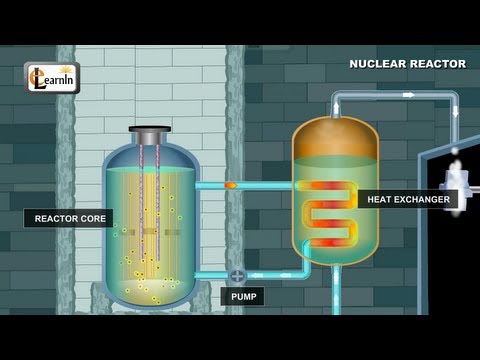

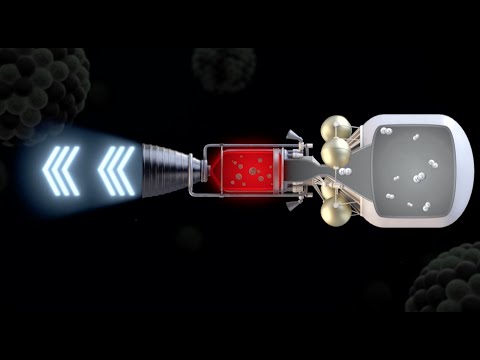

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) systems work by pumping a liquid propellant, most likely hydrogen, through a reactor core. Uranium atoms split apart inside the core and release heat through fission. This physical process heats up the propellant and converts it to a gas, which is expanded through a nozzle to produce thrust.

NTP rockets are more energy dense than chemical rockets and twice as efficient.

Engineers measure this performance as specific impulse, which is the amount of thrust you can get from a specific amount of propellant. The specific impulse of a chemical rocket that combusts liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen is 450 seconds, exactly half the propellant efficiency of the initial target for nuclear-powered rockets (900 seconds).

This is because lighter gases are easier to accelerate. When chemical rockets are burned, they produce water vapor, a much heavier byproduct than the hydrogen that is used in a NTP system. This leads to greater efficiency and allows the rocket to travel farther on less fuel.

NTP systems offer greater flexibility for deep space missions. They can reduce travel times to Mars by up to 25% and, more importantly, limit a flight crew’s exposure to cosmic radiation. They can also enable broader launch windows that are not dependent on orbital alignments and allow astronauts to abort missions and return to Earth if necessary.

NTP is not new. It was studied by NASA and the Atomic Energy Commission (now the U.S. Department of Energy) during the 1960s as part of the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application program. During this time, Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists helped successfully build and test a number of nuclear rockets that current NTP designs are based off of today.

Although the program ended in 1972, research continued to improve the basic design, materials and fuels used for NTP systems.

NTP systems won’t be used on Earth. Instead, they’ll be launched into space by chemical rockets before they are turned on. NTP systems are not designed to produce the amount of thrust needed to leave the Earth's surface.

Read more:

The Office of Nuclear Energy works with industry and other stakeholders to extend the life cycles of our current fleet of reactors and to develop new technologies that will help meet future environmental and energy goals.

Follow the Office of Nuclear Energy on social media:

---

NTP rockets are more energy dense than chemical rockets and twice as efficient.

Engineers measure this performance as specific impulse, which is the amount of thrust you can get from a specific amount of propellant. The specific impulse of a chemical rocket that combusts liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen is 450 seconds, exactly half the propellant efficiency of the initial target for nuclear-powered rockets (900 seconds).

This is because lighter gases are easier to accelerate. When chemical rockets are burned, they produce water vapor, a much heavier byproduct than the hydrogen that is used in a NTP system. This leads to greater efficiency and allows the rocket to travel farther on less fuel.

NTP systems offer greater flexibility for deep space missions. They can reduce travel times to Mars by up to 25% and, more importantly, limit a flight crew’s exposure to cosmic radiation. They can also enable broader launch windows that are not dependent on orbital alignments and allow astronauts to abort missions and return to Earth if necessary.

NTP is not new. It was studied by NASA and the Atomic Energy Commission (now the U.S. Department of Energy) during the 1960s as part of the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application program. During this time, Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists helped successfully build and test a number of nuclear rockets that current NTP designs are based off of today.

Although the program ended in 1972, research continued to improve the basic design, materials and fuels used for NTP systems.

NTP systems won’t be used on Earth. Instead, they’ll be launched into space by chemical rockets before they are turned on. NTP systems are not designed to produce the amount of thrust needed to leave the Earth's surface.

Read more:

The Office of Nuclear Energy works with industry and other stakeholders to extend the life cycles of our current fleet of reactors and to develop new technologies that will help meet future environmental and energy goals.

Follow the Office of Nuclear Energy on social media:

---

Комментарии

0:00:52

0:00:52

0:01:57

0:01:57

0:04:08

0:04:08

0:12:19

0:12:19

0:01:00

0:01:00

0:11:16

0:11:16

0:00:48

0:00:48

0:18:05

0:18:05

0:00:56

0:00:56

0:21:45

0:21:45

0:13:23

0:13:23

0:03:05

0:03:05

0:17:36

0:17:36

0:17:39

0:17:39

0:02:30

0:02:30

0:22:03

0:22:03

0:04:51

0:04:51

0:08:03

0:08:03

0:00:47

0:00:47

0:04:44

0:04:44

0:15:40

0:15:40

0:03:28

0:03:28

0:01:30

0:01:30

0:06:43

0:06:43