filmov

tv

Number Theory | Divisibility Basics

Показать описание

We present some basics of divisibility from elementary number theory.

Number Theory | Divisibility Basics

Number Theory | Theory of Divisibility | Fundamental Concepts and Theorems

DIVISIBILITY - DISCRETE MATHEMATICS

Number Theory Divisibility Proof

Number Theory Basics: Factors and Divisibility

Lecture - 1 | Basic Number Theory | Divisibility and it's properties | IIT JAM- CSIR NET- GATE ...

Elementary Number Theory: Definition of Divisibility

Fundamentals of Number Theory - Rules in Divisibility - Part 1

Unit #1 Lec07 Maths Paper I Number Theory - Divisibility | Jitesh Tripathi Sir | Mathvyas

Introduction to Number Theory, Part 1: Divisibility

Basic Number Theory: Divisibility. UVic Math 122.

Fundamentals of Number Theory - Rules in Divisibility - Exercises

Number Theory - Basics - Divisibility & Congruence

Basic Number Theory Divisibility Proofs for the Integers ℤ

Properties of Divisibility | Number Theory | Mathematics

Fundamentals of Number Theory - Rules in Divisibility - Part 3

Elementary Number Theory: Basic Properties of Divisibility

NUMBER THEORY. 'Properties of divisibility' (#2)

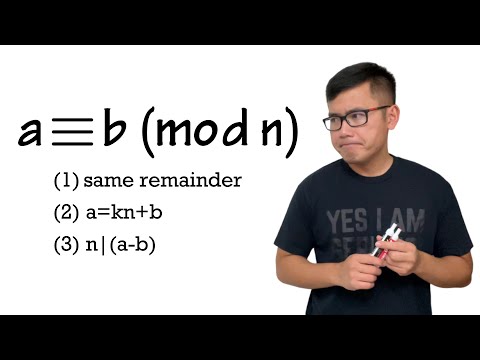

What does a ≡ b (mod n) mean? Basic Modular Arithmetic, Congruence

Fundamentals of Number Theory - Rules in Divisibility - Part 2

Lecture-1 Number Theory : Divisibility (Definition and Basic Concept) By Prof. TM Qadri

Number Theory (Divisibility)

Divisibility|| Elementary Number Theory|| Important results|| BSc Mathematics

[NUMBER THEORY] DIVISIBILITY 01

Комментарии

0:07:13

0:07:13

0:11:11

0:11:11

0:09:34

0:09:34

0:03:37

0:03:37

0:13:47

0:13:47

0:38:37

0:38:37

0:13:29

0:13:29

0:12:56

0:12:56

0:12:13

0:12:13

0:15:21

0:15:21

0:14:22

0:14:22

0:24:08

0:24:08

0:14:18

0:14:18

0:06:52

0:06:52

0:12:09

0:12:09

0:09:38

0:09:38

0:13:43

0:13:43

0:03:13

0:03:13

0:05:45

0:05:45

0:13:53

0:13:53

0:07:10

0:07:10

0:10:43

0:10:43

0:12:20

0:12:20

![[NUMBER THEORY] DIVISIBILITY](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/9krZHtYEkhg/hqdefault.jpg) 0:09:46

0:09:46