filmov

tv

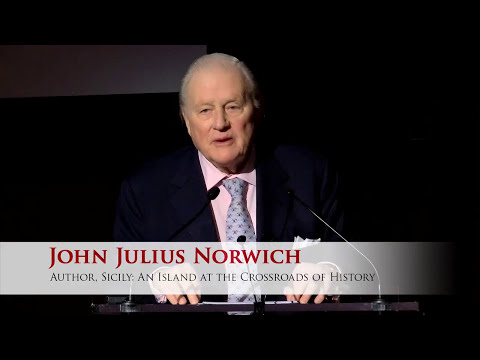

John Julius Norwich - The charm of Haddon Hall (131/136)

Показать описание

To listen to more of John Julius Norwich’s stories, go to the playlist:

John Julius Norwich (1929-2018) was an English popular historian, travel writer and television personality. He is the author of histories of Norman Sicily, the Republic of Venice, the Byzantine Empire and 'The Popes: A History'. [Listener: Christopher Sykes]

TRANSCRIPT: My Uncle John, who was the Duke of Rutland, had these two great houses. And it's quite a well-known thing, if you're interested in English country houses, that if by any chance a family has two, they're very apt to ruin the first one, the main one, but the second one they don’t spend much on or do much with, so the second one is nearly always far more beautiful than the first one. There are several cases in point I could mention, but I think, perhaps, the most important of all, really, is Haddon Hall, because Haddon Hall goes back to the 11th century, the oldest part of it. It's set in wonderful country, in the middle of the Derbyshire Peak District. And the family lived at Belvoir, which is 50 miles away, which was a huge mock Norman castle built in the beginning of the 19th century, and huge and impressive and magnificent, but by living there, they neglected this lovely, lovely old house. The last thing it had done to it, a long gallery was put into it about 15th century and nobody had touched it since. And it's of magical, magical beauty.

And then when my Uncle John, who was a remarkable, he was an antiquarian, and he decided, when he married at about 1910, I suppose it must have been, and he decided that he would live at Haddon. His parents were living at Belvoir and he didn’t want to live with them, he would move to Haddon. But Haddon had no hot water, it had no electricity, it had nothing. They'd just about kept the birds out, you know, and kept the roof on, but they'd done very, very little. It needed an enormous amount doing to it, not only to make it comfortable, but also structurally, for its own sake. And my Uncle John set to with a will, and he always said if you could see anything he'd done, he'd failed. Everything had to be invisible. And it's true, there's one huge great beam – there were three or four beams over the Great Hall – and one of them had to be replaced, but we still don’t know which it was. They all look exactly the same. And it could never be a comfortable house because I mean, you know, in the 16th century people didn’t know how to make comfortable houses, but it's of incredible beauty and it's got, I think, probably the oldest kitchen in England. It's got a 12th century kitchen, which is absolutely fascinating. It's got a huge great wooden chopping block, and then on the other side, the sort of working surface, it's just a thick shelf of thick wood, I suppose, about that thick, and at one end it's been scooped out into a sort of circular bowl just by hundreds of kitchen maids scraping away and, gradually, they've made a bowl out of it. And one day one of them went through the bottom of the bowl, so they moved a foot to the right and started a second one. And 300 years later, that went through the bottom too. They're now on the third one. And it's all there, it's all there, you can still see it now. It's absolutely fascinating. And my uncle, of course, was determined not to spoil this extraordinary survival, which meant building a new kitchen, but he didn’t want to spoil the house, so he built a new kitchen about 200 yards away in the hillside, underground, with an underground railway bringing the food up to the house. The food, of course, stone-cold by the time it arrived at the house, but, for him, that was a small price to pay for, as indeed it was, I mean, for this wonderful kitchen which still remains. And it's a very, very romantic house and, of all the houses in England, I think it's the one I would most like to possess.

John Julius Norwich (1929-2018) was an English popular historian, travel writer and television personality. He is the author of histories of Norman Sicily, the Republic of Venice, the Byzantine Empire and 'The Popes: A History'. [Listener: Christopher Sykes]

TRANSCRIPT: My Uncle John, who was the Duke of Rutland, had these two great houses. And it's quite a well-known thing, if you're interested in English country houses, that if by any chance a family has two, they're very apt to ruin the first one, the main one, but the second one they don’t spend much on or do much with, so the second one is nearly always far more beautiful than the first one. There are several cases in point I could mention, but I think, perhaps, the most important of all, really, is Haddon Hall, because Haddon Hall goes back to the 11th century, the oldest part of it. It's set in wonderful country, in the middle of the Derbyshire Peak District. And the family lived at Belvoir, which is 50 miles away, which was a huge mock Norman castle built in the beginning of the 19th century, and huge and impressive and magnificent, but by living there, they neglected this lovely, lovely old house. The last thing it had done to it, a long gallery was put into it about 15th century and nobody had touched it since. And it's of magical, magical beauty.

And then when my Uncle John, who was a remarkable, he was an antiquarian, and he decided, when he married at about 1910, I suppose it must have been, and he decided that he would live at Haddon. His parents were living at Belvoir and he didn’t want to live with them, he would move to Haddon. But Haddon had no hot water, it had no electricity, it had nothing. They'd just about kept the birds out, you know, and kept the roof on, but they'd done very, very little. It needed an enormous amount doing to it, not only to make it comfortable, but also structurally, for its own sake. And my Uncle John set to with a will, and he always said if you could see anything he'd done, he'd failed. Everything had to be invisible. And it's true, there's one huge great beam – there were three or four beams over the Great Hall – and one of them had to be replaced, but we still don’t know which it was. They all look exactly the same. And it could never be a comfortable house because I mean, you know, in the 16th century people didn’t know how to make comfortable houses, but it's of incredible beauty and it's got, I think, probably the oldest kitchen in England. It's got a 12th century kitchen, which is absolutely fascinating. It's got a huge great wooden chopping block, and then on the other side, the sort of working surface, it's just a thick shelf of thick wood, I suppose, about that thick, and at one end it's been scooped out into a sort of circular bowl just by hundreds of kitchen maids scraping away and, gradually, they've made a bowl out of it. And one day one of them went through the bottom of the bowl, so they moved a foot to the right and started a second one. And 300 years later, that went through the bottom too. They're now on the third one. And it's all there, it's all there, you can still see it now. It's absolutely fascinating. And my uncle, of course, was determined not to spoil this extraordinary survival, which meant building a new kitchen, but he didn’t want to spoil the house, so he built a new kitchen about 200 yards away in the hillside, underground, with an underground railway bringing the food up to the house. The food, of course, stone-cold by the time it arrived at the house, but, for him, that was a small price to pay for, as indeed it was, I mean, for this wonderful kitchen which still remains. And it's a very, very romantic house and, of all the houses in England, I think it's the one I would most like to possess.

0:04:41

0:04:41

0:03:46

0:03:46

0:00:57

0:00:57

0:01:42

0:01:42

0:09:44

0:09:44

0:03:28

0:03:28

0:03:18

0:03:18

0:00:36

0:00:36

0:52:19

0:52:19

0:03:16

0:03:16

0:04:25

0:04:25

0:01:15

0:01:15

10:39:24

10:39:24

0:02:02

0:02:02

0:02:19

0:02:19

0:02:12

0:02:12

0:06:03

0:06:03

0:02:50

0:02:50

0:02:06

0:02:06

0:02:12

0:02:12

0:02:46

0:02:46

0:01:29

0:01:29

0:03:15

0:03:15

0:02:39

0:02:39